Angie Farrow interviewed by Anastasia Bakogianni

AB: Angie, you teach theatre but you are also a successful playwright. Nowadays ancient Greek drama is viewed as the origins of Western theatre. How familiar are you with it and did it in any way impact on the two spheres of your working life as teacher and dramatist?

AF: I first studied Greek Theatre when I was a 19-year-old student. I struggled with Aeschylus because the language seemed so remote and the issues of his plays were beyond my comprehension at that time. However, as I became more immersed in the study of plays, I saw Greek theatre as the foundation. Studying the Greeks helped me understand how western drama had evolved. I love the simplicity of form. I particularly love the use of the chorus, the way it allows for the "big picture" perspective, how the chorus can be both commentator and victim of circumstance, how it is both the "I" and the "we" of the drama.

AB: Your first play was a parody of Greek tragedy. Tell us more about which ancient drama or dramas you had in mind and why did you satirize them? And of course how did you go about it?

AF: I was quite young when I wrote that play and I think it was my way of getting to grips with a theatrical form and language that still felt alien to me. Writing the play was a means of emulating the elevated language of the Greeks and trying to reach those huge universal issues and explore them in a contemporary context. The play was a commentary on the follies of materialism, but because the references were very local and domestic the play was a kind of send-up. I didn’t base it on any particular play, though I had been studying the 'Oresteia' and was compelled by the issues of justice and revenge and the interplay between gods and man. In my play, of course, the gods prevail and man succumbs to their uncompromising code of justice.

Chorus from Angie Farrow's Esther.

AB: The Greek chorus is an aspect of ancient Attic drama that modern directors have an issue with, although more recently that has been changing. Many of your dramas have a version of a chorus which suggests that this Greek theatrical device or form appeals to you. Tell us more.

AF: I spend a lot of time teaching the importance of chorus to my playwriting students. On the simplest level, the chorus can be a character of one who has the ability to look at the action dispassionately or with a sense of "big picture" perspective – the chorus often sees what other characters cannot. On a bigger scale, the chorus has huge theatrical potential. They dance, they sing, they provide a sense of the world beyond the drama, they are the crowd, the passers-by, the culture, the universal voice. They can enrich the stage with their rhythm and choreography. They can voice the play’s dialectic and give substance to the play’s thematic. The chorus can also provide the alienation effect that Brecht talked about: by standing outside of the action and commenting on it, they create a distancing effect that prevents the audience from becoming too emotionally engaged.

AB: You love big stories. There are mythical elements in a number of your plays. Any classical connections?

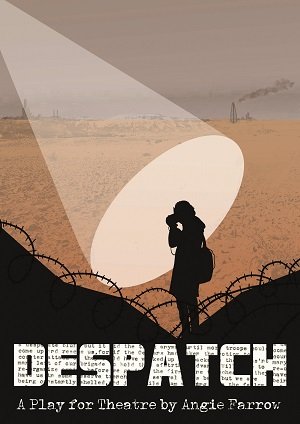

AF: I think all of my large plays try to address the big issues of the day. I’ve written about the problems around river pollution, the global refugee crisis, the issues of identity in multi-cultural groups ... In my play 'Despatch' I investigated the issues of war journalism during a genocide and was consciously attempting to achieve the epic scale of the Greeks. The major reference was 'The Bacchae' by Euripides. My protagonist, like Agave, is in a kind of trance of ambition, and it is only towards the end of the play, when she is confronted with a decapitated head of a friend, that the spell is broken. I included a character called Karastame who is a kind of god of war, merciless in his ability to kill and maim. He has, like the Greek gods, the potential to give life and take it away, and I used his power to resolve the narrative.

AB: In recent years you have been writing short plays. Are there any classical echoes lurking behind the surface of some of these short plays?

AF: I suppose I am always interested in telling stories where destinies are shaped and where big things happen in compressed time-frames, as in Greek drama. Many ancient Greek dramas follow Aristotle’s "action-in-one-day" rule, and this is a great device for intensifying stage events. Characters arrive on the stage often at the point where something is about to explode: past enmities or misdemeanours meet the present action on the stage and something has to give. The Greeks celebrate this intensity of action in space and time, and because my plays are often very short, I’ve been able to borrow a lot from the Greeks. One of the most recent plays I wrote is called 'Esther'. It comprises a chorus, a series of monologues and dialogues, and is set out just like a Euripides play. It observes the unities of time, space and action. While it doesn’t reference a particular play, it borrows entirely from Greek theatrical form.

AB: Let us switch hats now and talk about your teaching practice. When you teach performance do you ever get your students to work with ancient Greek dramas? What is their reaction?

AF: Yes, we always include a Greek play in the first year of the Drama in Performance course. The students seem to enjoy the Greeks and while they sometimes struggle with the language, the themes and narratives resonate with them. I’ve had significant success staging 'Medea', 'The Bacchae' and 'Agamemnon'. The students often have no difficulty discovering their relevance or finding metaphors that will enhance the theatrical performance. We once staged 'Agamemnon' with ship’s ropes, using them in a host of ways such as tug-of-war, as ship’s masts, as shackles, as decoration as snakes and so on.

AB: Greek drama has experienced a real renaissance in modern theatre. Do you think New Zealand is ready for some more Greek drama?

AF: The issues that are raised in Greek drama are always pertinent to our current situation. It is a question of finding directors who have an interest and who like working on a mythic scale. I think we live in troubled times and the Greeks had a way of fearlessly facing the difficult issues of the day, looking down the throat of the monster, so to speak, and daring to face up to painful reality. The Greeks ask us to look beyond the immediacy of our own circumstance and to reflect upon universal truths.

AB: And one final question: if you had to pick one Greek tragedy or comedy that you would like to see performed in New Zealand, which one would it be?

AF: 'The Bacchae'. The relationship between the forces of liberalism and extreme conservatism seem to be playing out on our global stage and no one seems to know what to do about them. This play not only explores these issues graphically, viscerally, rationally, but ultimately offers a solution. It is a play that teaches as well as a play that reaches us emotionally.