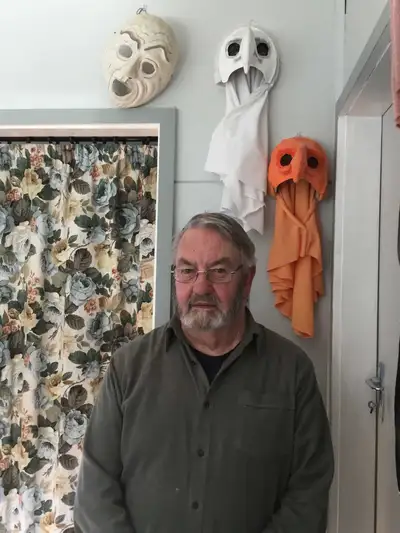

Dr Harry Love

Harry Love interviewed by Anastasia Bakogianni

AB: What drew you to Greek drama initially and why did you want to stage it in New Zealand?

HL: I was asked by the University of Otago’s Classics department to direct a Greek play in 1994. I chose Sophocles’ 'Oedipus Tyrannus' and then set about finding an appropriate translation. Among the many I looked at, there was none I would, as an actor, have felt entirely comfortable with. So I took a risk and wrote my own. And as you might imagine, the process of translation gets you closer to the essence of a play than someone else’s version ever could. This also, as it later transpired, resolved possible copyright problems when it was decided to film the productions.

AB: You have worked with both university students and professionals in your productions. How did your actors respond to these ancient Greek dramas? Can you recall any memorable occasions during rehearsals?

HL: Actors of all kinds, professional or amateur, react well to the ancient Greek plays. They are challenging even for experienced professionals and require intense focus to achieve the required disciplined expression of emotion at least as much as, or perhaps even more than, Elizabethan drama. Yes, there were memorable rehearsals, especially those moments when an actor breaks through to find something you had not been aware of.

AB: What challenges did you as a director face in adapting plays that are nearly 2,500 years old? What accommodations did you have to make to make them ‘speak’ to contemporary, local audiences?

HL: When I first set about translating the text of 'Oedipus' I was too clever by half. Prof Andrew Barker, to whom I gave my first draft, laughed loudly and asked where Sophocles had got to. He had been supplanted, as it turned out, by T.S. Eliot. ‘Just let the text speak for itself,’ he said. So I did, insofar as it is possible to do so, and the result is what you get in my translation. The only real adaptation that the tragedies need to be understood by a modern audience is the obvious linguistic one. The theatre itself is of course different, but not to a degree that it affects the character of the text. Relevance is there in the emotional substance and shifting levels of perception in the interaction between stage and audience. You do not need to hang a contemporary ‘issue’ on to the story to make it relevant. The comedies, though, are a different matter.

AB: You staged Sophocles’ 'Antigone' twice. What attracted you to this play specifically and why do you think it remains so popular today?

HL: In some respects it might have made more sense to have left 'Antigone' to follow the two Oedipus plays. However, pressure from various quarters, from school teachers and from potential cast members, as well as a feeling that I would like to revert to Sophocles after two Euripidean plays ('Hippolytus' and 'Bacchae') prevailed. My first production was performed and filmed in 1998. The second production, with a quite different cast, except for myself moving from the role of Creon to that of the Guard, 10 years later (2008) was also something of an audition for the principal actor (Kitty August) for the role of Agnes in the 'Hurai' (my adaptation of 'Bacchae') the following year. In its own right, themes of tyranny and conflict between the sexes make the play at least superficially popular. There is, of course, much more to the play than that and, given the current state of politics in New Zealand, especially the power of a kind of religiosity of thought in conflict about such things as race and freedom, there is much of relevance in the battle between Antigone and Creon.

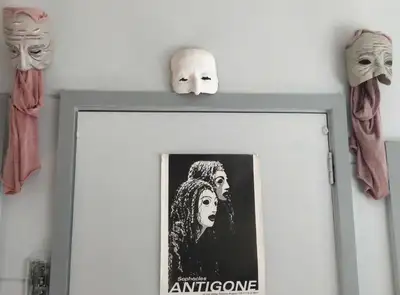

Poster of Harry's production of 'Antigone' and three of the masks used in his productions.

AB: Your favourite Sophoclean tragedy is 'Oedipus Tyrannus'. Tell us why, and what you most enjoyed in bringing the play to life onstage.

HL: I have directed 'OT' twice, the second time with mother and son in appropriate roles. However, it was also my very first Greek play, and I was fortunate to have a remarkable actor playing Oedipus: Ralph Johnson. He played Oedipus again in 'Oedipus at Colonus' (2000) and then Strepsiades in 'The Clouds' (2019). Ably supported by Marilyn Parker as Jocasta (she since played four other roles in my productions), a powerful cast and some exciting music (hearing the fourth stasimon still evokes that prickly sensation), he could reduce an audience to silent tears. It was, however, only after some time and more experience with a range of plays that I came to appreciate the 'OT''s intensity – seldom has so much been packed into a relatively short play. Both language and structure are compact yet clear, so that emotion is not merely evoked, but its various strands and their meaning in the action as a whole are vividly displayed. The scene of Jocasta’s revelation, with the overlapping emotional strands from Oedipus, the Messenger and the chorus, is for me one of the high points of the drama.

AB: Of Euripides’ plays that you staged, which is the drama that most ‘speaks’ to modern audiences? Tell us why and how you brought it to life.

HL: 'Bacchae' is the play that most people consider Euripides’ finest, but for me, the two Hecuba plays ('Hecuba' and 'The Trojan Women') are even more powerful. Unlike Sophocles, who can work on his audience’s emotions, Euripides assaults them. Almost invariably he elicits sympathy for a character then turns it on its head, somehow complicating the comfortable complacency of pity for the oppressed, whether Phaedra’s lie, Medea’s infanticide or the blinding of Polymestor. 'The Trojan Women' is, perhaps, an exception with its relentless descent into chaos and despair. There is, as I have suggested elsewhere, a Beckettian quality in Euripides’ plays that feels very modern.

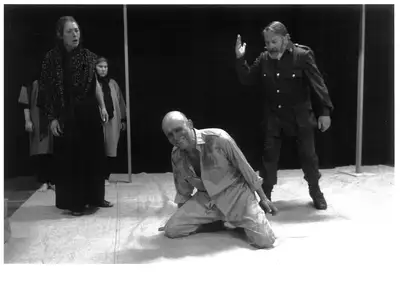

A still from the production of 'Hecuba' (2006): Hecuba (Vivienne Aitken), Polymestor (Michael McLeod) and Agamemnon (Harry Love).

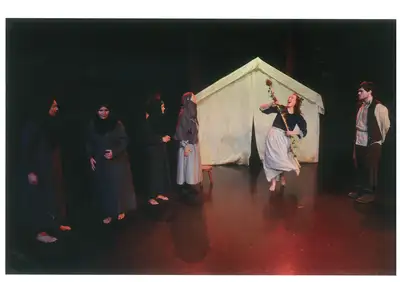

A still from the production of 'The Trojan Women' (2013): Cassandra (Megan Housley) with the torch, observed by Hecuba (Marilyn Parker), Talthybius (Dan Goodwin) and the chorus.

AB: Did you ever stage an Aeschylean tragedy? Is his work less accessible to audiences today?

HL: No; I considered it at various times, but I think that Aeschylus’ dramas require a different approach than those of the two other ancient tragedians. As important as the gods are in Sophocles and Euripides, it is the humanity of the characters that is foregrounded and that makes them more accessible to modern audiences. I would love to make an attempt. Unfortunately, given the ever-expanding bureaucracy of our universities, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to do so.

AB: What challenges did you face when filming your productions? Did you approach the process any differently?

HL: Before filming 'OT' I had been in front of a camera numerous times, but never behind one. The play was filmed over the course of one weekend with one camera by people who, fortunately, did know what they were doing. Two days of rapid oscillations between terror and elation ensued. All the plays after that were filmed by the University of Otago’s audio-visual unit, usually over a couple of days near the end of the run when the cast was, hopefully, at the top of their game. The principal adjustment for the players was to get used to the camera space, always much tighter than actual stage space. On the whole, however, actors adjusted quickly and easily, enabling the cameras to exploit the kind of close detail that is not so obvious on stage. There was, I think, a gradual progression from ‘filming a performance’ to something more like a ‘film’.

AB: Greek dramas were created to be performed. Why do you think that these ancient plays continue to be staged, adapted and filmed today?

HL: One of the remarkable things about Greek tragedy is that its apparently rigid conventions – episodes punctuated by stasima, the chorus as a character, lyric passages, messenger speeches, stichomythia (the rapid exchange of one-liners), etc. – are so much more versatile than they might at first appear. Their theatricality is obvious to any practitioner who reads a script. More than that, however, is their innate dramatic character – by which I mean the complex interaction of dramatic distance between stage and audience and the interplay of understanding and emotion that gives the plays their particular power. It is an aesthetic mode invented by the Greeks and it became the foundation of European theatre. It may have been submerged from time to time, as, say, through most of the nineteenth century when the novel was dominant, and theatre was more immersive spectacle than dramatic experience. It is a written mode that, as the Elizabethans discovered, found a voice through forms derived from both popular entertainment and religion.

AB: Who is your favourite tragic hero and/or heroine? Explain your choice to our readers.

HL: An impossible question for me to answer.

AB: The Greek chorus is an integral part of Greek drama. How did you portray it in your productions and what are your thoughts on its role in modern performances of these ancient plays?

HL: The chorus is an integral element in Greek drama and, in some respects, the most difficult aspect for a modern director, or audience for that matter, to deal with. Its original choral function does appear to contain some remnants of earlier rituals, but by the time of Sophocles and Euripides, the dramatic function of a composite character within the world of the play predominates. I have not had the experience of trying to replicate the conditions of the original productions, nor access to the appropriate theatrical space to make such an attempt. A chorus of 12 to 15 would have been too large for the spaces I had available to me, not to speak of the strain on my limited budget. Filming, too, might have been quite a different proposition. My first two productions had choruses of six members, who sang or chanted and were choreographed into, I hope, appropriate patterns of movement. My focus tended to be on the words. Since then, I have had choruses of three, which enabled me to place even greater emphasis on the chorus as a character in the drama.

AB: In some of your productions you used masks or half masks (covering the upper half of the face). What led you to this decision and how did it work on stage?

HL: I used masks in two productions, 'Antigone' (1998) and 'Oedipus at Colonus' (2000). Dionysus had a hand-held mask for the prologue and for the deus ex machina later in my production of the 'Bacchae'. For 'Antigone' only the chorus wore masks whereas the rest of the cast had heavily painted white faces for a mask-like effect. It was to an extent an experiment to see how actors could cope with masks (the chorus found them a bit uncomfortable to wear). What I had hoped to achieve was a kind of distancing effect, though it is very difficult to know how successful that was. They did, however, look good. For 'Oedipus at Colonus' I used half masks principally because I thought it would be too much to expect a cast that had no experience of performing in masks to use full masks (apart from the protagonist, that is). In both cases masks and makeup did infuse a degree of formality into the action, pushing actors away from their habitual naturalism. In 'Oedipus at Colonus' a mask also enabled me to visualise the profound effect on King Theseus of Athens’ farewell to Oedipus (a deposed and disgraced ruler). I would like to have used them more often, but they were expensive to produce.

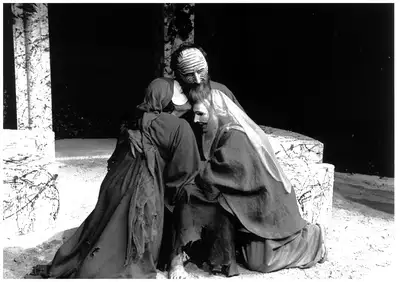

A still from the production of 'Oedipus at Colonus' (2002): Oedipus (Ralph Johnson) and his daughters Antigone (Julie Edwards) and Ismene (Lorina Harding).

AB: You made music and song an integral component of your productions of Greek drama. Do you think that these elements are still essential in staging these ancient plays?

HL: I think music is important and I have been fortunate to have some excellent composers contributing their talents to my production. In general, music elaborates the emotional context of the action, usually as felt by the chorus, though sometimes in counterpoint to the words they sing. If possible, I have had a preference for live instrumental accompaniment, allowing the musician to, in a sense, join the chorus. Unfortunately, it has not always been possible. Different instruments create different textures; flute and guitar for my first production of 'Oedipus Tyrannus', flute and glockenspiel for 'Hippolytus', oboe for 'The Bacchae', cello for 'Medea', soprano sax for my second production of 'Oedipus Tyrannus', guitar and drums for 'Hecuba', and violin for 'The Trojan Women'. And I learned, rather later than I should have, to find a chorus of singers who could act a bit, rather than actors who can sing a bit. That at least was the experience of 'The Trojan Women', the Euripidean play that, in my view, most closely rivals 'Oedipus Tyrannus' for sheer power and the last tragedy I directed.

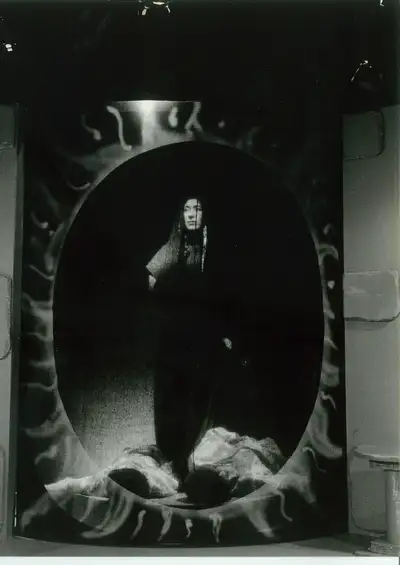

A still from the production of 'Medea' (2002): Medea (Vivienne Aitken) standing over the bodies of her two sons.

AB: Is there an ancient Greek play that you wanted to but never got a chance to stage?

HL: If I were considerably younger and had sufficient financial backing (both of which are equally unlikely), I would love to tackle Aeschylus’ 'Oresteia'. I would work closely with a composer and take time to explore and experiment. Ideally, the end result would be performed in the piazza of the Mediterranean garden in Dunedin’s Botanic Gardens.

AB: After creating such a memorable list of credits for productions of Greek drama, do you have any further plans to adapt and stage any more ancient Greek plays in the future?

HL: I have retired from the stage, so alas no.

Publication

Anastasia examines Harry Love's oeuvre and in particular his 1998 production of 'Antigone' in a chapter titled "Antigone in Aotearoa: Performing Sophocles’ Tragedy in New Zealand" in 'Re-embodying and Rethinking Greek and Roman Drama in Modern Times', eds. Alena Sakissian, Eliška Kubartová and Hallie Marshall. Brill (2024) 120-150: https://brill.com/display/title/70010