Interview with J L Pawley by Anastasia Bakogianni

AB: Jessica, let’s make a beeline for the classical references in your work. My first question to you is how and why did you choose the name 'Generation Icarus' for your protagonists. Did you have the myth of Icarus in the back of your mind and, if so, how familiar are you with the classical myth?

JLP: When I first settled on the story’s central concept of humans growing wings, I knew I did not want it to slide into paranormal fantasy, especially angel versus demon theology, as there are already thousands of books in this genre. However, I needed some kind of species name for my protagonists to give them a distinct identity, and avoid the cliché and stigmatised use of the term "mutants", which has been overused in several big movie franchises. I wanted something original, so I began searching for a new name that could become as familiar as, say, "vampire", "witch", or "mermaid", yet wasn’t a bunch of random syllables. Inventing an entirely new terminology would lack appeal to people who dislike hardcore fantasy, which can be overwhelming with its entirely made-up languages, maps and mythologies. The whole point after all was to entice reluctant readers and appeal to today’s teenagers! This new name needed to have a clear etymology, so that the majority of readers would instantly get an idea of what the story was about.

I was very familiar with the legend of Icarus from my childhood books, and the myth has reverberated throughout Western pop culture across the millennia. Art, music, even video games and heavy metal bands reference the story. The more I searched for any kind of non-angel mythological creature with a human form and birdlike wings, the more often Icarus would pop up in my search results. I played around with the name for a while, and realised that its Greek origins and Latinisation (from Ikaros to Icarus) slotted in perfectly with the scientific practice of binomial nomenclature, using the classical languages to name new species. I also liked the symbolism of Icarus’ wings being man-made, and the parallels with the genetic experimentation which altered my characters’ DNA and led to the creation of their wings. Eventually, the rightness of the fit became more and more obvious.

On my Google travels I came across our own species, as anatomically modern humans, being informally referred to as Homo sapiens sapiens to distinguish us from our extinct cousins who are also labelled Homo sapiens. That was the lightbulb moment for my own personal neon sign! Henceforth, my new species of humans became Homo sapiens icarus. I would refer to an individual as an Icarus and, thanks to the Latin courses I took during my degree, the plural would be Icari. The series title Generation Icarus came to me not long afterwards.

AB: Classical mythology has proven extremely durable and remains popular to this day as demonstrated by the work of, among many others, Rick Riordan and his 'Percy Jackson' novels. Your reception of the classics, however, differs from his as your books are not intended as modern versions of the ancient stories. Can you tell us more about the role the classics played in your world-building?

JLP: While I am aware of the classics and their influence on modern storytelling practices, I was adamant from the very beginning that my story would not be an adaptation of any particular myth, even that of Icarus himself. Not least because of the ongoing popularity of 'Percy Jackson' and other novels, as you say! I wanted my story to be grounded in the real world and not rely on gods and magic. I also wanted to be as original as possible, inasmuch as established writing conventions allow. Of course, many of these said modern conventions we owe to the classics, from the hero’s quest to the three-act plot structure to thematic quests and symbolism. It’s inescapable, and it is part of the reason why the classics are still studied today, thousands of years later.

My Icari, who call themselves "The Flight", aren’t out to save the world. There’s been a flood of such stories in the last 10 to 15 years, and the challenge of inventing an original global threat for heroes to overcome is resulting in an over-saturation of increasingly ridiculous and outlandish plots to which many audiences can no longer relate. However, the classics often tell stories of a hero’s quest to overcome a very personal challenge, often to escape an unpleasant situation and get back home. Or even simply to find a home. The protagonist’s struggle to find his own identity, to prove himself, to overcome personal obstacles (be they monsters or royal mothers-in-law) is a journey that everyone can relate to. Modern teenagers are coming of age in a world that the ancients couldn’t imagine, but, symbolically, their individual quests to discover who they are and to find a safe place to grow and flourish in this volatile global village reflects the struggles of many ancient heroes. It is the same path that my own characters must follow, by foot or by feather.

However, there are also a number of conventions that I wanted to smash with a very large hammer. The main characters in my story, for example, are teenagers of both genders and different sexual orientations and socioeconomic backgrounds, from all over the world – a far cry from the standard white adult male soldiers, kings and poets who dominate Western mythology. Additionally, legends often portray morality and ethics as very black-and-white. The monsters are bad, the humans are good. Humans are subject to the whims and wills of the gods, which they accept as the natural order of the world. Of course, reality is never that clear-cut, and my characters, being non-human, are faced with the challenge of being accepted into a world that is struggling with equality in every imaginable facet of society.

AB: In the ancient world, stories existed in many versions, none of which were set in stone. Do you feel that in a way you are following in the footsteps of the ancient Greeks adapting familiar stories for new audiences?

JLP: My journey towards becoming a published author is quite unusual and very reflective of our modern digital age, particularly compared to 20th-century novelists. In fact, I have more in common with the oral storytellers of old and Charles Dickens than the living authors whose books I grew up reading in the 1990s. Thanks to the advent of the smartphone and the sudden onslaught of ebooks around 2007 to 2010, which is when I started writing, it became almost impossible to find a publisher willing to offer a contract to a new author. Such a prize was and still is akin to winning the lottery. So I found myself experimenting with self-publishing and ended up serialising the series on the streaming ebook website/app Wattpad.

This platform is dominated by romance and fan fiction, but as a sci-fi author I did manage to carve out a small niche, in which eventually nearly 1 million pairs of eyes would discover my books. The best part of this ebook host, however, is that it allows readers to comment directly on the text, to talk to each other and the author about their immediate reactions to the story as they read it. In my Master’s thesis I argued that a comparison can be drawn between this new technology and oral storytelling when a performer would entertain an audience who could visibly and audibly respond to the twists and turns in the tale as it unfolded. Because of this close contact, the storyteller/creator could adapt and adjust either as they were telling their story, or for their next performance. Similarly, in Victorian England, the original serialised release of each "chapter" of Charles Dickens’ stories would often be read aloud by the literate members of a social group to the rest, and their responses would travel far and wide among the community and eventually back to the author himself. Dickens is known to have altered the significance or actions of certain characters in subsequent releases of his work in response to his audience’s feedback.

Moving on to the 20th century, increasing levels of literacy led to the increasing isolation of both author and reader, as authors would labour alone on their manuscript (or with relatively minimal feedback from editors and friends) before the book was released into the world as a whole, unalterable entity. In contrast, my use of Wattpad to release early versions of my books online meant I began receiving direct feedback from readers before I was formally published. Their reactions led to several rewrites and updates to the books (another wonderful advantage of the streaming nature of the platform), and assisted the evolution both of the story and of myself as a writer. It also helped me be discovered by my publishers Stream Press, an imprint of Eunoia Publishing. The final published version of the story is similar to that which I originally drafted in the summer of 2010–2011 with regard to general plot and character, but has been developed and improved a hundredfold, almost as though I have adapted and retold my own story, just as the classics evolved and were retold over time.

AB: In your view, how familiar are your readers with the classical story? Have any of them commented on your treatment of it?

JLP: It largely depends on how widely they have read before they pick up my books. Voracious readers like me are usually familiar with it, but when I successfully lure in those who are a little more reluctant, they've often never heard the name Icarus, let alone the ancient story itself. This is why my characters openly discuss the myth in the first book, and read a brief summary of the story to each other (and the reader) to make sure everyone is on the same page. Because it’s not a direct adaptation, few have commented on my treatment (at least, not directly to me), but I’m sure many savvy readers have picked up on the themes and references I’ve scattered throughout the text.

AB: Your novels are largely set in the United States, but feature an international cast. One of your favourite characters in the series is Tui, a Māori girl from Auckland. What do you feel she adds to the story that is distinctive and challenges ancient Greek views and portrayals of women?

JLP: Diversity is something the ancient tales lack, as we were discussing before, and I feel very strongly that this is a key issue that still needs to be addressed in our culture. This series is my effort to crack open the door a little wider for our sisters and brothers of colour. When I started writing the books, I was wary of cultural appropriation and I was worried that my characterisations would be too stereotypical, simply because of my lack of life experience and skills (I was 21 at the time). The feedback I received online from teenagers of colour, especially from the US, was hugely influential in my development and confidence, and I hope I have done my long-time loyal fans of all skin tones proud.

I knew from the beginning that I wanted a Kiwi character, and a strong female one at that. I wanted to show the world that New Zealand is not just a land of hobbits, and that our people can kick butt with the best of the contemporary international adventurers. And Tui, being proudly Māori, is in many ways the most grounded character in the whole Flight even though she's the one furthest away from her homeland. Unlike the white aristocratic women we encounter in ancient myths, she doesn’t muck around with meaningless words or manipulating men to get what she wants (or worse, just waiting for men to do it for her, or hopelessly falling in love and stumbling about messing everything up doing the exact opposite of what she was told to do). As a responsible and pragmatic paramedic cadet, Tui becomes the big sister of the Flight, looking after them as best she can and not taking any nonsense along the way. Later on she develops a very healthy relationship with an African-American Icarus from New York. There are no trust issues, no soppiness, and she’d rather jump off a cliff without her wings than be caught mooning about or compromise her integrity for the sake of a crush. Luckily, Falcon is more than happy to lavish her with respectful attention, learning more about her culture and making her laugh with his terrible jokes, and their steady low-key romance is one of my favourite side-plots of the books. Totally anti-classical, but I intended it as a distinctive and much needed addition to the modern canon of teen-targeted genre fiction.

AB: Any final word about the trilogy and its connections to the Classics before we draw this interview to a close?

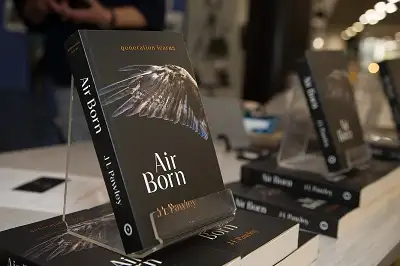

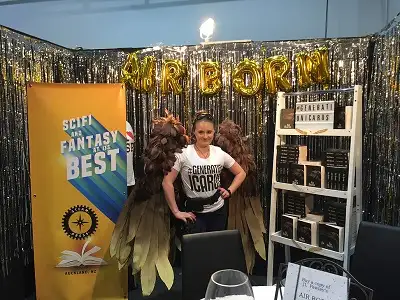

JLP: The most obvious clues are the titles of the trilogy which are, in order: 'Air Born' (2017), 'Take Flight' (2018, which won the Notable Book Award from the Storylines Children’s Literature Trust), and 'Sun Strike' (2021). The thematic similarities with the legend of Icarus are deliberate but are largely a symbolic nod rather than an indication that the characters are literally going to fly too close to the sun! However, there are some scenes in the books with very clear parallels between the ancient myth and my story that I’m rather proud of. Let's just say, heat proves a significant factor in the challenges facing the Flight in 'Sun Strike', and their very wings may fail them in the hour of their greatest need in the finale. But to find out what happens you have to read the trilogy!