Jennifer Lawn and Mary Paul interviewed by Anastasia Bakogianni

AB: The first play the students encounter on the ‘Tragedy’ course, taught at Massey University, is Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus. Why include a Greek tragedy at the start of the course?

JL: The course takes a chronological approach, so we start with the origins of tragedy in the Western tradition. We ask why tragedy emerged in the Greek cultural stream and not the Judaic cultural stream. We consider the influence of (i) the absence of the idea of ‘providence’ or ultimate divine rationality in the Greek cosmos (in the Christian tradition, the Story of Job is the closest that the Bible brings us to tragedy), and (ii) we take a lead from Albert Camus’ view that ‘tragedy flourishes when the pendulum of civilisation is halfway between man and the divine’. Then the course takes us to three other ‘bus stops’ in the quick tour of the history of tragedy: the Elizabethan period, post-World War II, and contemporary New Zealand.

It would be interesting as an experiment to teach a course on tragedy in reverse chronological order, i.e. starting with the contemporary examples and working our way backwards so that students work inductively from observations of tragic form, ending up with Aristotle’s view of tragedy and Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus.

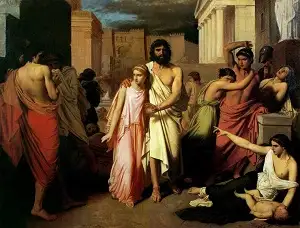

MP: I am currently teaching this exciting course. I found that the play got the students thinking about the idea of tragedy -and the way it might have changed- straight off. I concentrated particularly on the play as performance. We read and discussed it extensively with the students in preparation for their tableaux (examples appear in the video interview).

AB: My follow-up question is why Oedipus specifically? Is it because of Aristotle’s view in his Poetics that this particular Sophoclean drama is a model tragedy?

JL: It happens to fit very well with Hamlet (for the psychoanalytically inclined) and of course is brilliantly plotted. I’d also enjoy teaching Antigone, but would have to think carefully about whether it would work as well with the assessment, particularly the tableaux. It does seem to me that the figure of Oedipus had its cultural high point, so to speak, in the (long and still influential) era of aesthetic modernism. It resonates particularly to the elements of the Modern that revolved around speaking the truth to oneself and unbarring one’s origins. It does seem to me that the halcyon days of Oedipus (so to speak) belong to an era when authenticity – speaking the truth to oneself, unbarring one’s origins – was a central value in Western culture. Antigone might be more a play for our times, with its split understandings of authority and sovereignty. The ‘contest of laws’ is a constitutional challenge in postcolonial societies, and one that for those of us grounded in New Zealand cultural and/or literary studies impacts on how and what we teach.

MP: Oedipus Tyrannus is one of the course’s core texts. My own approach to teaching the play changed after I spoke with Anastasia. I didn’t emphasise Aristotle’s interpretation of the play as much as originally planned. Jenny explains at the beginning of the course that tragedy is defined very widely as a sad story and discusses the philosopher’s influential ideas. But Aristotle’s definitions of theatre and tragedy post-date the first performances of these plays. In the fifth-century BCE the genre of tragedy was more inclusive than his definitions suggest. On the other hand his categories are extremely powerful, and very influential on Western culture. They are well-laid out in the course and distance students draw on them extensively. I would guess that Aristotle’s opinion that Oedipus Tyrannus is a model of what tragedy should be is why Jenny chose it – and I would be interested in substituting Antigone. The students often became obsessed with the role of destiny (curses and oracles) and the power of the gods when they engage with the character of Oedipus and his story. It would be interesting to see how else it could play out, if they started the course by reading Antigone instead.

AB: How have the students you have taught over the years responded to the play? Do they find it has something to say to them or do they find it hard to engage with? What do they make of Oedipus and his journey of self-discovery?

JL: Yes, they find the play engaging and I’ve seen some wonderful creative work – both in the tableaux, and in the director’s notes where students have had the option to imagine a version of the play in any mode (theatre, film, puppetry, animation etc.), casting anybody dead or alive and with an unlimited budget! There are angles to the play that will catch on with just about anybody: you can focus on the family/relationship dynamics; the psychology of the tragic hero, an approach that students tend to be familiar with from high school; the more ritualistic elements as Mary says; the dilemmas of leadership, a big field of study across disciplines at the moment; or the related question of what appears to be the problematic revival (or persistence) of charismatic leadership and dynastic succession in contemporary contexts.

MP: The distance students who also studied or are familiar with Māori tikanga (culture) were interested in creating parallels in their production notes between Māori tribal configurations and Oedipus’s story. Popular themes included tribal origin stories, animism, epic scale, scope, and reverberations, and the key role memory plays in oral culture. The internal students were interested in the role of ritual and the role of the gods in theatre. This was a mind bending, light bulb moment for some, and Jenny’s notes and particularly the film of Oedipus (Oedipus Rex, 1957, directed by Sir Tyrone Guthrie) Anastasia shared with the students encouraged further exploration of these themes.

AB: Does the issue of incest between mother and son shock your students? What are their reactions towards Oedipus and Jocasta?

JL: Not every student actually knows the story, but there are so many spoilers online and in class discussion that I guess they generally find out before they actually read the play. I haven’t heard that they were shocked, as such, but we do look for signs in the play that Jocasta knows the truth (or at least intuits or gleans it) well before Oedipus. Some students have imagined Jocasta as a ‘scarlet woman’ (or a cougar!), heedlessly indulging her desires. It makes for great soap opera! Others see her as caught in a system where her choices are not her own to make, and where her body and mind have to be subordinated to the needs of the city and the people.

MP: On the whole they accepted the characters as being put on the spot by events. They were unsure or not so strong on the role of hubris in the play– though they did suggest that Oedipus might have fared better, if he wasn’t the sort of person to get into fights at crossroads. They were observant, noticing that Jocasta is in denial about Oedipus’s true origins, but on the whole they were very sympathetic to her situation, especially her original loss of her son. In general the students are often fascinated by the play’s back story and sometimes choose to include it in their tableaux. They were also interested in exploring the role of gender in the play. Some of the students have a background in Classics which they brought to our discussions.

AB: In your expert opinion, how influential have Freud’s views proved for students studying the play? Does the famous Oedipus complex impact their interpretation of the story and if so how?

JL: In general, I find that students tend to be sceptical of Freud. Some who are parents, particularly mothers, may have observed the development of gendered identity and children’s explorations of sexuality, so that can be one avenue of understanding based on experience. I approach the Oedipus complex as Freud’s attempt to explain how male heterosexuality is reproduced from one generation to the next. It’s Victorian gothic, really, based on the schema of an authoritarian father and an indulgent mother. I also discuss Freud in a class on gender politics in narrative structure across literature and film, and there’s no doubt that the Oedipal complex keeps returning – often in parodic or ironising ways in recent decades. Misogyny is widespread in Western culture, and psychoanalysis attempts to explain it – why men seem to punish and fear women, at a structural level, when women are virtually never a physical threat to men.

MP: Sometimes Freud’s views can limit students’ understanding of the play, but on the whole it is useful to discuss Freud’s use of the ancient story to illustrate behaviours he observed in his own society.

AB: How do your students deal with the ancient concept of moira (fate/destiny)? Do they find it an alien idea? Does it help shape their view of Oedipus and his actions?

MP: Debating the concept of fate is often challenging. Our students come from diverse backgrounds, which allow them to reflect on their own culture’s view on the question of fate and on how one should act, if one believes or has been raised with a moira /fate world-view. Such cross-cultural discussions greatly enrich our work with the play. We also talk about psycho-biology, epi-genetics and genetics, as new ways of believing in destiny.

JL: I agree with Mary. We talk about the human tragedy as being based partly in the fact that we have to act –make decisions, big and small– with no way of knowing what will eventuate from these actions. Modernity is characterised by an attempt to eliminate such guesswork, through the rise of the scientific method, risk analysis, biopolitics and demographic management, and so on. But there is a turn against such technologies now, or at least some resistance and scepticism.

AB: You are teaching a course that combines a close study of the selected plays with an emphasis on performance. How do you approach teaching a Greek tragedy? Does it differ in any way to how you teach the other plays on the course, which include Shakespeare and twentieth-century plays?

MP: I think inevitably it does. We focused on gesture and size in the tableaux format, with some reference to how the play was originally performed in the fifth century BCE. However in the production notes produced by the distance learners there were some examples of the domestication of the play – bringing it closer to a naturalistic style. I think studying a Classical play first is incredibly useful when we move on to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, because students understand better how theatre developed. We draw attention to the commonalities between Greek tragedy and Shakespearean theatre, the use of traditional stories, the role of intrigue, the back story, and the off-stage action, how the chorus was replaced by common opinion etc. This is an area that I would like to expand on in future presentations of the course.

AB: For their first assignment for the course the students are asked to create tableaux based on the Oedipus story. Can you explain the rationale behind this performative exercise?

JL: It was my Massey colleague Angie Farrow’s idea to start with the tableaux. It takes the anxiety of ‘learning the words’ out of performance, supports careful narrative analysis as students have to select key scenes, encourages students to think of their bodies and the use of space as the main resources for good theatre, and is done under time pressure – so students have to think quickly of an idea that unifies their production and illuminates the play as a whole, and pull together as a group to advance that idea in genre/style, mood, selection of scenes, transitions between scenes and the blocking/composition of the pose in each scene. It’s optional for them to include the chorus – sometimes depends on how many students are in each group. One year students opted to perform it in a group of about nine, and that was wonderful because each scene was so visually rich and the chorus were able to enhance the emotional impact of each scene.

MP: I did think it is very effective. It made students focus on gesture and narrative, and to reflect on the importance of collaboration in theatre; all important elements for performance.

AB: Have you ever considered replacing Oedipus Tyrannus with another Greek play? If your answer is yes, which one would you choose?

MP: Yes, with Sophocles’ Antigone, but it would mean rewriting the course. I hope that such classical elements will remain key components of our courses in Theatre Studies.

JL: As with Mary. Medea might be good too, but then I think the course might require different plays in the 20th and 21st century sections of the course. I would have to think about that some more.

AB: Let’s finish on a personal note: based on your experience of teaching Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus do you like the play and why? If, on the other hand, you are not a fan, tell us why?

MP: I enjoyed it, getting to know the play better, discussing it with students and Anastasia, and reading what scholars and theatre critics had to say about it. However, personally speaking I have found other ancient Greek plays I have seen more interesting.

JL: I’ve increasingly appreciated the irony and humour in the play, but also feel that it is time to develop other paradigms in the course.

Acknowledgements: With sincere thanks to the groups of 'Tragedy' students (Auckland campus, 2017) who gave their permission to be recorded performing their Oedipus tableaux.