Kelly Harris interviewed by Anastasia Bakogianni

AB: You directed an adaptation of Euripides’ 'Medea' titled 'The Book Club' in 2016. What drew you to this particular Greek tragedy?

KH: I first stumbled upon Medea at University, while studying Greek tragedy. Many years later, there was a real wave of the Greek classics being reimagined and performed by large theatre companies around the world and this reignited my passion for the classics. At first, I wanted to direct the ancient play itself, but as our company is interested in experimental work, devising, and strong female roles, we decided to use the text as a starting point to create a bigger piece about the lives of modern women.

AB: Do you think 'Medea' can still speak to modern audiences? Did you, at least in part, adapt the ancient play in order to make it more accessible for a New Zealand audience?

KH: Absolutely. A play must speak to its audience for it to be true art. At first glance, Medea might be hard to relate to, but when you peel back the layers and look deeper at her decisions and influences you discover many ways to sympathize and understand her. We questioned why might a modern woman be reading Euripides’ 'Medea'? This sparked our idea about a book club. We created a provocative scenario: what if eight women from completely different backgrounds all came together on one stormy night to discuss 'Medea', the play? We also looked at important issues facing women in today’s society – the most important one being our need to wear masks which conflict with our need for equality. In a male-centric society, all women are outsiders, much like Medea. Women are constantly trying to achieve and find contentment in a world where they still have to fight for equality and self-worth. Through workshops and improvisation, we were able to mirror the modern and the ancient Greek worlds. As the women discuss the play, there are flashbacks to Medea’s story. All the women play Medea at some point during the play and all the women’s issues reflect those that the ancient tragic heroine is experiencing, such as rejection, being an outsider, betrayal, love, nurture, motherhood and so on.

AB: Are ancient plays hard to stage in New Zealand? How did audiences react to your version of the Medea story?

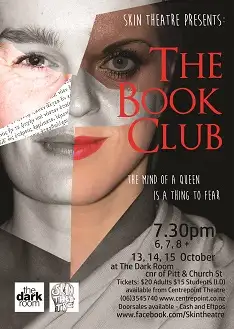

KH: Audiences will always question: how does this relate to me? Greek plays are difficult for modern audiences to accept because they cannot always see a clear and relevant connection. It is the artist’s role to bridge the gap between the world of the play and the audience’s own reality. It is difficult to stage classic plays in Palmerston North because the competition (such as local comedies, musicals) seem more appealing. I believe that good concepts and innovative publicity can change this though. The way we approached the text and how we chose to promote our play meant that we appealed to a wider audience and also unearthed new interest. In particular, we opted for a "stripped back" and very "classic" approach with our publicity – no makeup in profile photos, images in black and white, a big presence on social media and so on. We had fantastic reviews for our show and our audience found the experience very emotional. Here are some quotes from reviewers and our audience members:

An exceptionally effective team... their choreography is free-flowing even in the small Dark Room space. The one-hour play is a devised work by cast and crew, a meticulous collaboration which, to borrow a line from itself, ‘ticks all the boxes.’

Tina White – Manawatu Standard

This is a remarkable piece of work ... it is performed magnificently by the actors individually and as an ensemble. Enthralling and compelling, 'The Book Club' is a terrific achievement and begs a sequel.

Richard Mays – The Tribune

So moving, emotional and powerful ... I was left so hungry for more.

– Audience member

Have just gotten home from watching this flawless piece of art! Was emotional and deep, a little dark at times ... But truly impressive. Would recommend to all the ladies and artistic gentlemen lol.

– Audience member

Well done Kelly and team. This was a high impact theatre experience and we are so lucky to have your company working in the Manawatū. I can’t wait to see the next project. There was a lot of great discussion with my girls as we unpacked this afterwards.

Del Costello – Tall Poppies Group

The Book Club rehearsal.

Preparations for staging a New Zealand version of Medea's story

AB: Which translation of the play did you select for your adaptation and why?

KH: We used Philip Vellacott’s 1963 translation for Penguin Classics. This was the version I used when I studied the play. I adapted the text by editing it down to approximately 10 pages, which closely followed Medea’s narrative. I also included the Chorus and some lines from Jason and Creon.

AB: In 2011 and 2015 you spent some time in London studying and learning at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre as part of the Shakespeare Globe Centre’s New Zealand’s education programme. While there did you become aware of the current popularity of Greek drama on the London stage?

KH: Yes. I was privileged to see the Almeida’s 'Oresteia' in 2015. This production was 3 hours and 40 minutes long with three intervals! I loved how simple their aesthetic was and how they made the world of the play feel modern but still inherently epic and the tragedy unrelenting. I was also aware of The National Theatre’s own version of 'Medea', having come across images online, and could see that their approach was similar. Ancient plays aren’t being performed enough in New Zealand. This was another big motivating factor for me.

AB: Can you tell us a bit more about your creative process? What did the rehearsal period involve?

KH: We initially started the process with discussions and brainstorming then ran a series of workshops with the cast and crew. We explored aspects of Medea, then women in the 1950s, and finally modern women now. During these workshops we relied heavily on improvisational activities, including character hot seating and creating chorus moments using lines from 'Medea'. After the workshops, we decided to focus on Medea and the modern woman, and brainstormed possible narratives after we had the book club idea. We would meet on weekends and improvise scenes, and during the week I would write the scenes up and work on character depth one on one with the actors. Sometimes I would write a scene or bring an idea to rehearsals first and then the actors would trail it.

As we progressed and characters gained more depth we continued to tweak the script until it was finalized. We explored a variety of themes and this led to a lot of discussion. An integral part of the process is personal reflection. This was often done at the end of a session or after an intense scene – sometimes the women would write ‘in role’ or from their own personal perspective. They were encouraged to share extracts and listen to each other’s perspectives.

The murder of the children in 'The Book Club'

AB: A key question that every production/adaptation of Medea’s story has to confront is why she decided to kill her children. How did you deal with this difficult issue?

KH: We tried to maintain a balance between sympathy for Medea and an acknowledgment that Jason makes some valid points. We explored the idea of adultery and how gender influences the audience’s sympathy for the tragic heroine. In the modern world, a female character admits to cheating on her husband, but finds sympathy in the all-female group because she was trapped in a terrible marriage. This is contrasted with Jason’s decision to marry the princess to seek a better future for their children. This allowed the audience to make their own moral judgement on this point. If someone is betrayed, does that gain him or her any sympathy when they decide to take revenge?

We found that age and experience was a factor during our workshops and that is the perspective we presented in our play: some of the actresses were mothers, others were young and not thinking about having children. This evoked thorough and rigorous discussion. However, in general, the women found it hard to comprehend Medea’s actions. They felt that a mother’s instinct to protect her children should have prevailed. The youthful voices in the company also advocated strongly for women’s rights and a desire to speak up for oneself. We also introduced a character who had an abortion, to engage with the question of to what degree does our modern society accept a woman’s right to make this decision? While not the central focus of the play, it did add to the difficulty of the question and inevitably what it means to be a modern woman. Everyone has their limits and a point beyond which they cannot be pushed. Research into child abuse and cases of infanticide supported our belief that societal pressures, mental health issues and environmental factors can lead even the best mothers to make some very cruel decisions.

AB: In ancient theatre violence usually took place offstage and was reported by a messenger. In 'Medea' the audience heard the children’s cries as their mother killed them, but they did not witness it on stage. How did you stage the murder of the children?

KH: We chose to represent the moment of murder on stage using metaphor/symbolism. At the back of the stage, we had a community notice board covered in posters made up of hundreds of images of women. One poster had two young boys on it. During the murder, Medea moves in slow motion, grabs the picture, tears it in half, and lets it fall to the ground as the chorus of women try and stop her, but eventually they relent. This was a moment of heightened poeticism reinforced by lighting and music.

Medea and chorus from The Book Club.

The Greek chorus and the use of masks

AB: In your production you adopted some of Greek drama’s theatrical conventions. Most notably, some of your actors used masks and you retained the Greek chorus. How did your adaptation benefit from drawing on these ancient theatrical conventions?

KH: The use of masks and the chorus proved critical to the success of the production. We used these conventions from the very beginning, in all our workshops and rehearsals. These conventions, while stunning on stage, also work as excellent devising tools, helping us to explore character and dialogue in improvised moments. One of our cast members, Kristin Reilly, is a qualified choreographer. Her innovative chorus direction and leadership meant that the work was energetic, interesting and meaningful. The chorus is an essential tool for creating strong ensemble work. It helps to bring the cast closer together and allows them to work as one. We experimented with the use of masks during rehearsals and found that women wearing masks pretending to be men didn’t feel right. We discovered that holding the mask up was more effective. Our masks were hidden inside books that "popped up" when opened – linking them with the concept of the book club in visual terms and also with the idea of the world of the play "popping" up in the present.

AB: At the end of Euripides’ 'Medea' the tragic heroine escapes on a dragon chariot. How did you conclude your version?

KH: Ultimately, we discovered that Medea and Jason are two sides of the same coin. Jason betrays Medea and then she betrays him by murdering their children. They are both flawed. We presented this symbolically by having Medea and Jason mirror each other’s actions. After she tells him that she has done this "to break your heart", the Greek world reverts back to the modern day and it is revealed that Nadine, the woman running the book club, has actually lost custody of her children after a drink driving charge. This exposes how women can "lose" their children in the modern world even when they love them. This also allows the audience to see that there is a dichotomy between what people see and what is really happening. We see that Medea is a strong, powerful woman but she makes this horrible choice. We see Nadine as a strong, modern woman but she too made a choice to drink and drive. A lot of people in the audience can relate to this moment of weakness and this helps the audience reach their own verdict on Medea.

A modern interpretation

AB: In your view Medea is mentally unstable. Can you share with us how this interpretation influenced your version of the story?

KH: Medea is fragile and gives in to her weakness. She has been forced from her home and has been betrayed. We worked hard to sympathize with her because, as women, we knew that we would also be heartbroken if we were in the same situation. We chose to look at a variety of different women, who like Medea are all struggling to "fit in" the society they live in. We had an overworked young mother, a woman who cheated on her husband, a woman who is childless because her husband didn’t want children, a young woman who is fiercely feminist, a woman who sees herself as a failure, a woman who is an outsider because she is gay, a mother who is tired of her children and wants her old life back, and a woman who looks like a superwoman but is breaking apart inside. All of these women reflect aspects of Medea and how the desire to maintain an "ideal" or "perfect" facade can be so quickly destroyed.

AB: From a modern perspective Greek tragedy used very little stage scenery. Can you tell us more about your setting and use of props?

KH: These are gritty plays where few props are needed. It is Skin Theatre’s practice to use minimalist sets and props. Our focus is always on ensemble work and physical theatre. We set up 'The Book Club' in a community hall, established by a series of eight graffiti chairs and a noticeboard where posters about women’s issues are on display. We used books, including copies of 'Medea', masks, and news reports. A baby doll symbolized motherhood as well as the children themselves in one scene.

AB: Do you have any plans to stage/adapt another classical play?

KH: At this stage we do not have any immediate plans but we have entered our script in the Playmarket Adam NZ Playwriting Award.

AB: Good luck!

Sincere thanks to Kelly’s collaborators Maree Gibson, Lana Sklenars, Catherine Tubby, Maggie Webster-Shadbolt, Jessica McLean, Kristin Reilly, Sasha Lipinsky and Hannah Pratt.