Rand Hazou

Derek Gordon

Rand Hazou interviewed by Anastasia Bakogianni

AB: Rand, tell us how you became involved in staging Sophocles’ 'Antigone' in an Auckland prison. As a classicist I also can’t help but ask, why did you choose this particular Greek tragedy? And are you aware of the drama’s illustrious history of performance in prisons, for example in South Africa under apartheid?

RH: Derek [Gordon] and I had previously worked with a particular unit at Auckland prison on a project that involved devised performances. This was a forum theatre project directed by David Diamond that involved devising three short plays based on the experience of the prisoners of social justice issues. During this project, a couple of the prisoners had expressed some interest in working with an existing text, and rehearsing and staging a play.

When Derek and I began discussing possibilities, Derek was originally very keen on Shakespeare. However, we were both a little unsure how much the language would constitute a barrier for the men’s engagement with the play. Our thoughts turned towards Greek tragedy and to 'Antigone' in particular for several reasons. I had previously directed the play as a student production in Melbourne and found it such a wonderful platform for getting inexperienced students thinking about physicality – especially given the important role the chorus plays within the drama. The tragedy also explores the primal and universal desire to respect the dead with appropriate rites and the sacred obligation to provide them with a dignified transition from the land of the living to the world of the ancestors. In this way, we thought, the play resonates culturally with Aotearoa. Māori tikanga are well-known for their rituals and protocols to deal with the dead, and we hoped the conflict in 'Antigone' would be immediately recognised by Māori and Pākehā alike. I wasn’t particularly aware of the play’s production history or its history of being performed in prisons in South Africa under apartheid. But I am not surprised given that the play raises important questions about ethics, standing up for what is right, and not bowing to authority.

AB: How did your volunteer performers respond to Sophocles’ drama? What challenges did they face in performing this ancient play that is more than 2,500 years old?

RH: The group we were working with volunteered to be involved in this theatre project. In other words they were not forced to engage with theatre and each member was there by choice. This meant that there was a very positive engagement from the performers. Nevertheless we did face some challenges – particularly around some of the language. The men in the prison theatre group have a wide range of literacy levels, so we needed to find a way into the text that made sense to the members of our group. Although we chose to do a Greek tragedy instead of a Shakespeare play to avoid problems with language, in the end we also didn’t want to rely on a translation that did away with the poetry of the drama. After some discussion we decided to use the translation by H D Kitto (1962), since we thought this translation achieved a good compromise of using language that could be easily understood by the cast, but which also held onto some of the poetry of the drama and hence some of its "otherworldly" qualities.

AB: How did the prison’s authorities respond to your proposal to stage 'Antigone'? After all, Greek tragedy deals with some pretty big problems and many revolve around the theme of crime and punishment. Did the prison authorities raise any specific concerns about the ancient material? Did any of it strike them as particularly controversial?

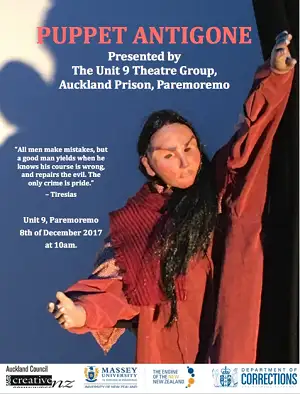

RH: When we pitched the idea of the play to the prison authorities, we explained that we wanted to do a puppet version of Sophocles’ 'Antigone'. The authorities were not so concerned about the Greek play but they were worried about the idea of half-life-sized puppets being used. Some of the inmates we were working with were sexual offenders, and the prison authorities were particularly concerned that some of these men might be quite literally "handling" and manipulating the female form. We had suggested the use of puppets because we wanted to create a piece of physical theatre in order to develop the physical skills of the performers. The use of puppets was also proposed as an innovative approach to staging the female characters within the all-male prison environment.

I have to admit we were worried that by cross-casting gender roles we might end up spending a lot of time dealing with jokes and anxieties before actually getting down to working with the female characters, and this was time that we didn’t really have. But we argued that the physical requirements of handling the puppets (particularly given we wanted them to be bunraku-style puppets which require more than one operator) and the effort involved in coordinating their movements would promote a sense of care and respect from the participants. Once we explained our rationale and our way of working, the authorities came on board.

AB: Specifically on the use of puppets for Antigone and Ismene, can you tell us more about this element of the performance? How did you help your performers engage with this form of theatre?

RH: We thought that by using puppets for the central female characters we could avoid unnecessary feelings of discomfort from the men who were used to an environment that forced them to perform particular types of male gender roles. We definitely wanted to avoid the joking around that cross-casting and cross-dressing would inevitably give rise to. So we proposed the use of puppets to get around this problem. We also thought that by designing bunraku-style puppets we might force two or three of the men to work together quite closely to bring one puppet alive. We were fortunate to be allowed to invite Kate Parker to give the men an introductory puppetry workshop. Kate is a well-known puppeteer and one of the founding members of Red Leap Theatre. This workshop developed the cast’s physical performance skills as well as getting them thinking about how to animate objects, and how to invest them with character traits and intentions.

AB: Your theatre group performed the play in English using Kitto’s translation as your performance script. Can you tell us a bit more about how and why you abridged, adapted and tailored the text?

RH: Early on in the process Derek created a stripped-back version of the play, rewriting it so that it could be more easily understood by the participants. However, after some discussion we decided to go back to using Kitto’s translation. We wanted to hold on to some of the poetry of the drama – to emphasise that this is not the "everyday" world.

We faced many challenges engaging with the text in rehearsals. The performers we were working with had very limited acting experience and some members of the team were on medication and had problems memorising their lines. Time was also a key determining factor. The script we ended up using was a heavily abridged version of Kitto’s translation. We ended up following this text quite closely, although we did occasionally re-word key sentences or opt for a contemporary translation of a key phrase so that our performers could connect with the meaning of the text.

We also made changes when the cast thought that the audience (a mixture of visitors and other prisoners) wouldn’t be able to follow the story. For example, in Act I, the guard delivers the captured Antigone to Creon, and describes the funerary rites she performed for her dead brother. In the Kitto translation the guard explains:

…then at once

Brought handfuls of dry dust, and raised aloft

A shapely vase of bronze, and three times poured

The funeral libation for the dead.

(427-31)

In our discussions with the cast, it became clear that they thought that the term ‘funeral libation’ would not be understood by the audience. In the end, we changed it to:

… then at once

Brought handfuls of dry dust,

And scattered the earth upon the body…

To give you another example, when Antigone is being ushered off by the guard after being sentenced by Creon to imprisonment, she exclaims in Kitto’s translation:

You princes of Thebes, O look upon me,

The last that remain of a line of kings!

How savagely impious men use me,

For keeping a law that is holy.

(940-43)

The cast thought that the word "impious" would be unfamiliar to most people, so we changed it to "unholy".

AB: The performance included some wonderful music by one of the inmates. How did this element come to be part of the performance?

RH: We were very keen to use live music. However, since we were entering into this project without a clear idea of the musical talents of the cast, we were unsure how we would go about facilitating this. In the end one of the cast members, Prickles (not his real name), not only told us he had good composition skills, but was also keen to take on the role of musical director. We were more than happy to give him the responsibility and the opportunity.

During our read-through of the play, we discussed how sections of text, particularly the lines of the chorus, might be sung by several cast members after being arranged by our musical director. In the end Prickles, who is a very talented performer, ended up singing all the musical interludes accompanying himself on the guitar. All the song arrangements were given a blues feel, a musical style that lends itself wonderfully to the laments of Antigone’s chorus.

AB: One last question, Rand. Reflecting back on the experience of introducing theatre in an Auckland prison, why do you think it matters? And was there anything in particular you felt your volunteers took away from being involved in a performance of Sophocles’ 'Antigone'?

RH: In our project briefs and in conversation with the prison authorities we tend to avoid claims about the rehabilitative nature of the arts. Personally speaking, I am sceptical about the idea of reducing the arts to a utilitarian function. Instead, when we described the aims of the theatre project we emphasised things like providing a creative opportunity for inmates to cultivate their emotional, physical and literacy skills, or providing an opportunity for participants to develop confidence and attain a sense of achievement and fulfilment by presenting their creative work to an audience.

Derek and I both believe that the arts can have redemptive and therapeutic qualities, but we tend not to emphasise this in the work we do in prisons. Instead we focus on things like building trust and team-working skills, and in the end, it is through these kind of skills and abilities that we see real value in this work. For example, one of the key features of our rehearsals was a trust circle that brought each session to a close, where every member got the chance to say whatever they liked. The role of the rest of the group was to listen with respect. During these moments, a sense of a working ensemble emerged, as various cast members would take other members to task for not being prepared enough or for not learning their lines. This was done with an honesty of spirit and a comraderie that was refreshing. We often wondered whether the men were given enough opportunities to critique each other without it being defensive or aggressive. We thought there was great value in this as it allowed various members’ insights into their own abilities and potentials.

Privacy clause

Please note that the names of all the prisoners involved in the performance of 'Antigone' are withheld and their faces are obscured in the accompanying video. We wish to respect their privacy, but take this opportunity to congratulate them once more on all their hard work and a wonderful performance.

Publication

Anastasia examines Rand Hazou and Derek Gordon's 2017 adaptation of Antigone in a chapter titled "Antigone in Aotearoa: Performing Sophocles’ Tragedy in New Zealand" in 'Re-embodying and Rethinking Greek and Roman Drama in Modern Times', eds. Alena Sakissian, Eliška Kubartová and Hallie Marshall. Brill (2024) 120-150: https://brill.com/display/title/70010