Associate Professor Gina Salapata speaking at the Symposium of Gastronomy.

By Associate Professor Gina Salapata.

The ancient Greeks loved wine and considered it an important product of their civilisation. They certainly didn’t think there was anything wrong with drinking, but they did recognise the hazards of alcohol when used improperly.

The wine was a gift from the powerful god Dionysus, son of Zeus and the mortal princess Semele. Dionysus was an ambiguous and contradictory deity: together the gentlest and the most terrible; god of the living and the dead; male but sometimes of “feminine” appearance; bringing peaceful coexistence with nature for his devotees but destructive madness to his opponents. Contradictory traits were also seen in wine which needed to be handled with care.

The philosopher Socrates praised wine, “Wine moistens and tempers the spirit and lulls the cares of the mind to rest. It revives our joys and is oil to the dying flame of life.”

Greeks, at least the males, were introduced to wine at a young age. During a spring festival, when new wine was brought into the sanctuary of Dionysus to be tasted, small jugs were given to boys in their third year from which they sipped their first taste of wine. This marked their formal admission into the religious community. The jugs were decorated with vignettes from the life of toddlers, like some modern christening mugs.

In ancient Greece, wine was offered as a sacrifice to gods on different occasions, for example, to ensure a good harvest. It was also drunk by common people at festivals, weddings and other festive occasions. It was especially consumed during the symposium: a private affair celebrated mainly in the elite homes in a room set aside for that purpose, the men’s quarters, which was lavishly decorated.

The guests, almost always men, reclined on couches placed head to foot along the walls of the room. This arrangement facilitated interaction because everyone could see each other and avoided hierarchy by giving equal importance to all.

The symposium was part of the Greek identity, but it was strictly a male activity with respectable women not allowed to participate. In this patriarchal society, women were considered particularly susceptible to wine and unable to control themselves.

The symposium was governed by established rituals and rules. First, participants were served dinner, at the end of which the tables were replaced, hands washed, garlands put on and some neat wine offered to the gods (including Health, the daughter of the god of medicine Asclepius). We still say “Yia sou!” (Greek) or “Salud!” (Spanish).

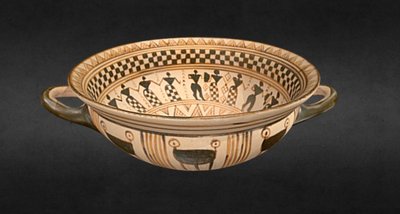

Then it was time to get down to the real business - drinking wine. Pottery cups were frequently used while metal ones were for fancier parties.

In Ancient Greece, Pottery cups were frequently used to drink wine.

They imbibed in rounds, so the consumption of wine was equitable. The wine they drank was not neat. It was mixed with water in a deep bowl to a strength dictated by the host of the event. The usual ratio was five parts water to two parts wine, so more like having wine with your water than water with your wine.

The undiluted wine was not stronger than the wine of today but mixing it with water allowed drinkers to enjoy its benefits while maintaining composure and self-control, traits that were highly valued in Greek society. They aimed for that delicate balance between relaxation and inspiration and intoxication. Getting inebriated was certainly not the end goal. Even in Greece today, most people drink slowly and with food and drunkenness is frowned upon.

Indeed, moderation played a central role in ancient Greek culture. For them, moderation meant knowing your limitations and acting accordingly, avoiding excesses and pursuing balance in life.

Drinking unmixed wine was considered uncivilised. Only barbarians, a term they used to refer to non-Greeks, drank their wine neat, got drunk and behaved like…barbarians.

During the symposium, the men were entertained by dancers, flute players, acrobats and courtesans who offered “earthly pleasures”. Participants would tell stories, sing poetry and hymns and engage in lively conversations and philosophical debates. They could perform drinking songs of a bawdy nature, sometimes competitively with someone saying the first part of a song and another improvising the end of it.

They would also play party games like the kottabos, which was quite a messy activity. The players looped a finger through one handle of the cup and flicked the wine dregs at a target, which was usually a metal disk balanced on the top of a pole in the middle of the room, to bring it crashing to the ground. In another variation, there was no metal stand; rather, the goal was to sink small dishes floating in a larger bowl of water. There were, of course, plenty of slaves to clean up the mess.

All this turned the symposium into a shared social experience that was facilitated by moderate drinking which relaxed the participants, lowered inhibitions and allowed them to enjoy each other’s company.

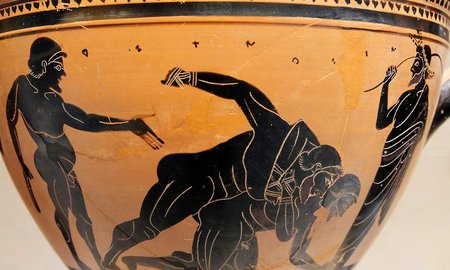

Warnings about excessive drinking could be passed on to the drinkers through mythical episodes depicted on cups and mixing bowls. A scene from Homer’s Odyssey decorates the inside of a drinking cup. It shows the encounter of the hero Odysseus with the Cyclops Polyphemos.

On the way back from Troy, Odysseus and his companions reached the land of the uncivilised Cyclopes who were living in caves and tending flocks because they had not learned yet about agriculture. He went to Polyphemos’ cave. Contrary to the rules of hospitality, he ate two companions for dinner and two for breakfast. Odysseus offered neat wine to Polyphemos who became drunk, ate two more companions and fell asleep. Then the hero drove a stake into the Cyclops’ eye and blinded him.

One of the main morals of the story is the dire consequence of drinking: ignorance of the powers of wine (especially neat) can destroy even a ferocious monster. Imagine the impact such a scene would have on the drinker who sees it at the bottom of his empty cup.

But the most interesting guidelines on how to drink wine come from the god's own mouth via Eubulus, a comic playwright of the fourth century BCE.

Dionysus says, "For sensible men, I prepare only three mixing bowls: one for health (which they drink first), the second for love and pleasure and the third for sleep. After the third one is drunk up, wise men go home. The fourth bowl is no longer ours but belongs to arrogance; the fifth leads to shouting; the sixth to rudeness and insults; the seventh to black eyes; the eighth is the policeman’s; the ninth leads to vomiting; and the tenth to madness and the hurling of furniture.

Isn't this a very wise and eternal message? The Greeks were not against drinking, but they knew and respected their limits. I’ll drink to that!

Associate Professor Gina Salapata's research revolves around Greek art, archaeology and religion.

Related news

The Olympics: When athletes were men, nude and Greek

The Olympic Games have a rich history: The inclusiveness of Tokyo will be a world away from their origins in Ancient Greece where men from only the city states of Greece competed nude after prayers and sacrifices

What can the Ancients teach us about merging and mixing?

Democracy and citizenship are ancient ideas, still evolving in our time. Massey University Classical Studies specialists will share insights on how outsiders were integrated into Ancient Greek and Roman societies and explore parallels and pointers for today's world.