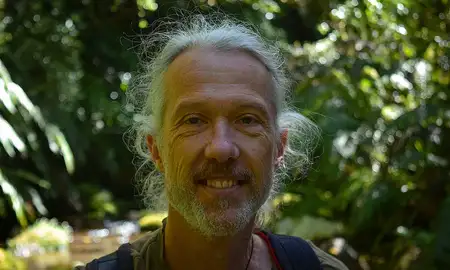

Black robin/karure/kakaruia (Photo by Emeritus Professor Doug Armstrong).

The black robin, also known as karure (Moriori) or kakaruia (Māori), have become a symbol for successful conservation and perseverance after returning from the brink of extinction. In 1980, there were only five left in the world and only one single breeding pair known as Old Blue and Old Yellow. Through the work of a dedicated team and a foster species, the Chatham Island tomtit/miromiro, the black robin population numbers were able to improve over three decades.

Their dramatic rescue and road to recovery is far from over however, as there are now new plans to secure their survival.

Black robins are currently split between two populations. There are around 270 black robins on Hokorereoro/Rangatira Island, with the numbers being reported as stable to slowly increasing indicating the approximate carrying capacity of the island. On Maung’ Rē/Mangere Island, the average population over the last two decades has sat around 40, hitting 50 at its peak, but the numbers dropped to about 20 in the last few years with a male-biased sex ratio.

With the recent decline in the Mangere population, along with the increased risk of having the only other population being near carrying capacity, a high risk of extinction remains.

This led the Department of Conservation to refocus recovery efforts to secure the future of the species. Planning began in 2021 with a community and expert workshop held on Rēkohu/Wharekauri (Main Chatham Island) that confirmed the need to assist the Mangere population through a top-up translocation of 10 females. A model of the Mangere population developed by Massey alumna Dr Liz Parlato was a critical component in this process as it showed how, without any intervention, the species could be functionally extinct at this site within four years.

In September 2022, the catch team began the translocation process. The first nine days of the trip on Rangatira Island was spent feeding and training the birds, using meal worms to coax them into the traps to get them accustomed to the process. Given the time of year, the females were constantly pestered by the males, making it difficult for them to feed and many were initially wary of the traps.

The female birds were identified using the band colours on their legs, and their sexes were known from DNA extracted from feather samples taken several months earlier during banding when they were juveniles.

The team managed to catch the 10 females close to the landing area within the first two hours of transfer day, making for an easier transfer onto the boat for the 45-minute trip to Mangere. The birds were released by early afternoon on the same day.

Translocations include a high risk to individual animals due to the stresses involved in capture, holding, transport, and being moved to a new environment. The Mangere population is being monitored daily, with seven of the 10 translocated females being seen regularly, a good sign for how they’re adapting to their new home.

Emeritus Professor and Oceania Chair of the International Union for Conservation of Nature Conservation Translocation Specialist Group Doug Armstrong was part of the translocation team. He says it was special to get to have a role in the world-famous story of the black robin recovery.

“I’ve been involved in reintroductions for 30 years, but had never been to the Chathams before, so to be a part of this was a bucket list moment for me.”

Emeritus Professor Doug Armstrong with the first catch of the 10 translocated females (Photo by Dr Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes).

Three other members of the team included Dr Kevin Parker, who led the project, Dr Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes, and Senior Biodiversity Ranger Erin Patterson, who all studied with Massey before continuing onto their careers as conservation experts.

Re-establishing further viable populations in other sites is also important as inbreeding depression is a concern, with the whole species descending from Old Blue. Offspring of closely related individuals can suffer from reduced biological fitness, resulting in reduced chances of survival. The occasional translocation of birds to other sites can help reduce inbreeding depression as well as the probability of the existing population declining due to reaching the carrying capacity of the island, and the risk of two limited populations being eradicated due to natural disaster or disease.

While Tapuaenuku/Little Mangere Island is the last site the species lived before intervention, a recent visit has shown the habitat there is not currently able to support black robins.

A further outcome of the 2021 community and expert workshop was an agreement to progress the establishment of black robin populations on Rēkohu/Wharekauri (Main Chatham Island) and Rangihaute/Rangiauria (Pitt Island), to reduce the risk of extinction and increase community connection to the species. There are currently workshops in effect to plan for future opportunities in this space.

Before further translocation plans can be made, one or more sites on these islands must be properly prepared. This includes setting up predator-exclusion fences and mammalian pest eradications, as both islands are inhabited by introduced mammals and people, as well as seeking agreement from the Department’s treaty partners and community.

It’s an ongoing process and a long, continuing fight for population recovery of the black robin. With the dedication of the experts involved and the support of the public, there are hopes that the black robin population will continue to grow and remain an example of just how important conservation is to the preservation of our endangered native birds.

Related news

Massey researchers help to reintroduce Robins to Turitea Reserve

Toutouwai, North Island robin, are locally extinct in most of their original range but thanks to a collective community effort including several Massey University researchers, a successful translocation has taken place to reintroduce the bird in the Manawatū Turitea Reserve.

Ecology award the first given to a Massey recipient

Professor Doug Armstrong from the School of Agriculture and Environment has been awarded the 2021 Te Tohu Taiao Award for Ecological Excellence.

Kākāpō brain surgery a world-first

A young kākāpō chick has undergone life-saving brain surgery at Massey University's Wildbase Hospital to treat a developmental problem of the skull, a world-first procedure, adapting surgical techniques from humans and other mammals.