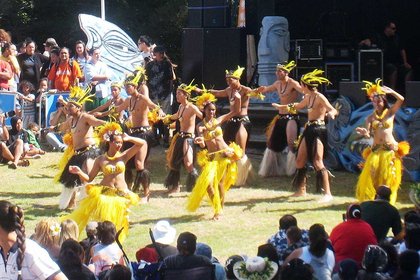

A quarter of young New Zealanders identify with multiple ethnicities including Māori and Pasifika, but this is not captured in data collection, according to new research (image-Auckland Pasifika Festival/Wikimedia Commons).

A quarter of young New Zealanders identify with more than one ethnic group, mostly as a mix of Pākehā, Māori and Pacific Island backgrounds through parental marriage, migration, ancestry and cultural affiliations.

But new research from Massey University has found that government data collection methods, especially in education, could be distorting policy and funding decisions because they fail to allow people to register full details of their multiple ethnicities.

Dr Philippa Butler’s doctoral thesis in social anthropology is on the topic of people who identify with more than one ethnic group, why they do so, and what this means for them in their everyday lives. Her thesis, titled Negotiating multiplicity: Macro, meso and micro influences on the ethnic identifications of New Zealand secondary school students, has implications for education policy and funding priorities, she says. Dr Butler, who graduated at the end of last year, wanted to find out how the boundaries between the macro (state), the meso (institutional), and the micro (family and individual) levels of ethnic identifications become blurred or blended across home, school and other scenarios.

Her research was sparked by the observation that; “in New Zealand, the number of people who identify with more than one ethnic group is increasing, but there is little understanding of what this means for individuals.”

Her study highlights ethnicity as a “socially constructed phenomenon” based on self-identification and social ascription that reflects how “cultural affiliations can be multiple, and can change over time and according to context.”

The project involved a national survey of Year 12 students about their ethnicity, as well as field research at South Auckland secondary school Kia Aroha College, where the ethnic and cultural identities of the student population are celebrated and nurtured as a core component of the school’s philosophy.

Dr Butler, a research officer at Massey’s Institute of Education at the Manawatū campus, says young people who are encouraged to embrace the fullness of their multiple ethnic identities are more likely to be confident, strong, happy, resilient people – that was the conclusion of her in-depth interviews with five students from Kia Aroha College, which actively encourages the development of students’ cultural identities and home languages, in two distinct ‘schools’ within the campus – Te Whānau o Tupuranga (Centre for Māori Education) and Fanau Pasifika (Centre for Pasifika Education).

But her study reveals that the ethnically rich, diverse identities of school students are not captured in official data gathering methods – and that is a concern, she says, because the information used to inform funding priorities for teaching and learning may not be tailored to the needs of the students.

Dr Phillipa Butler's doctoral research shows government data does not allow for multiple ethnic identities to be recorded.

How the system captures data

Dr Butler says that in meeting the Ministry of Education requirement to gather ethnic group data about each of their students, schools can record up to three groups per student. However, schools can report only one group per student to the Ministry. Identification as Māori is first priority, followed by Pacific groups, Asian groups, other ethnic groups, European groups, and finally, those who identify as New Zealand European or Pākehā.

“The Ministry of Education does not allow multiple ethnic identifications, and does not allow individuals to choose which category they would prefer to be recorded under,” she says. In comparison, in the New Zealand census, “Statistics New Zealand does allow multiplicity, as long as people identify with ethnic groups that appear in different pan-ethnic categories. For an individual who identifies as Samoan and Tongan, for example, multiplicity is lost. They would be recorded as ‘Pacific Peoples’ only.”

In her survey conducted in 2011 and sent to Year 12 students in schools across New Zealand, responses from students at 54 schools showed the 732 respondents identified with 45 different ethnic groups. Of these, 533 (72 per cent) identified with a single ethnic group, and 199 (27.2 per cent) identified with more than one group. Interestingly, for 24.2 per cent of the respondents, the ethnic group or groups with which they identified were different from those they ascribed to their parents.

One respondent who identified as Samoan, Tongan, Māori and New Zealand European/Pākehā describes why she identified with her ethnic groups, saying she focused on “coming from an island background”, and did not specifically mention her Māori or New Zealand European/Pākehā heritage or cultures. The Ministry of Education prioritisation scheme allocates her to the Māori category.

“From her description, however, one could assume that, if asked to state a preferred single ethnic group, she would identify more strongly with either her Samoan or Tongan groups. In terms of Ministry of Education resourcing and policies, she would come under strategies targeted at Māori learners. However, these strategies might be failing to support her needs. She might be better served by being encompassed within strategies for Pacific Islands learners,” says Dr Butler.

Dr Butler says that part of her job as a research officer involves designing and administering surveys to students and teachers and other education stakeholders to gather data for various research projects.

“Given that ethnicity is an important factor in ensuring that educational provisions meet the needs of all students, these surveys often include a question asking for the respondents’ ethnic groups. Over the years, I have found that the ethnicity question is the one that generates a lot of comments – respondents use the ‘other’ comment box of an electronic survey or the margins of a paper-based survey to complain about the question or to write a long and detailed explanation of how they identify themselves and why.

“Asking for a person’s ethnicity is not a straightforward question, as people resist being put into simple boxes,” she says.