Associate Professor Gina Salapata presenting at the 2024 NZ Symposium of Gastronomy and Food History.

By Associate Professor Gina Salapata.

Last year, we marked the 50th anniversary of Classical Studies at Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University. The highlight of our celebrations of this important milestone was an ancient Greek banquet held at Wharerata restaurant on the Manawatū campus. It was a great gathering of over 70 diners, including colleagues, friends, Wharerata regulars and current and former Classics students.

For this unique event, I challenged my Greek friend and talented chef Nikos Moraitis to create a dinner menu using only ingredients found in ancient Greece. With my guidance, he delivered an impressive spread. It was quite a feat considering modern staples like potatoes, rice, pasta, lemons, tomatoes and sugar had not yet been introduced.

To help Nikos select ingredients for his menu, I researched ancient Greek diet and culinary practices.

Contrary to what modern dietitians claim about the benefits of a hearty breakfast, the Greeks traditionally began their day with a very light meal: some barley bread soaked in wine, sometimes complemented by figs or olives. Even today, most Greeks still opt for a light breakfast or skip it altogether.

The ancients would also eat pancakes, mentioned as early as 500 BCE, which were thicker than the crêpe-style pancakes we are familiar with and were served with honey and toasted sesame seeds or walnuts.

A quick lunch was taken around noon or in the early afternoon. However, the most important meal of the day was dinner, eaten at nightfall.

Men and women normally ate separately, with men eating first in smaller households. Wealthier homes had slaves to serve meals. But, as the philosopher Aristotle noted, "The poor, having no slaves, would ask their wives or children to serve food."

Cutlery was rarely used. Forks had not been invented yet, so people used fingers, knives to cut meat and spoons for soups. Pieces of bread were used to scoop food, soak up sauces or serve as napkins to wipe their fingers.

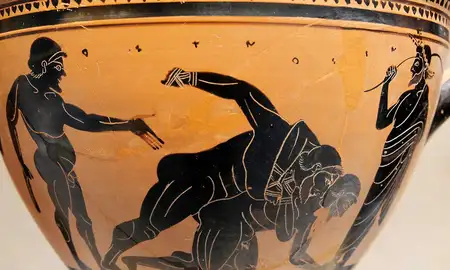

Wealthy, aristocratic men hosted banquets—symposia—in private homes in a room set aside for that purpose. Guests, male-only, reclined on couches placed head to foot along the walls, an arrangement that facilitated interaction. After dinner, they drank wine, which was always diluted with water to prevent intoxication and allow for more engaging conversation.

At the symposia, entertainment was provided by dancers, flute players, acrobats and courtesans. Participants shared stories, sang poetry and hymns and engaged in lively conversations and even philosophical debates.

Associate Professor Gina Salapata dressed up at the Wharerata banquet.

What ingredients and dishes formed the backbone of the ancient Greek diet?

The Greeks had relatively simple and frugal meals, much less extravagant than the Romans, who later introduced more gourmet dishes.

Grain products, primarily wheat and barley, were the foundation of the average citizen’s diet, with bread being a staple at most meals, similar to Greece today. Homer notably referred to the Greeks as “bread eaters.” They baked various breads, including flatbreads, yeasted loaves and coarse millet bread. Typically, loaves were flat, circular and indented into sections, as ancient wall paintings show.

The next largest food group consisted of fruits, vegetables and legumes like broad beans, lentils and chickpeas. Common vegetables included asparagus, mushrooms, onions, leeks, garlic, carrots, turnips, radishes, cabbage, lettuce, celery, cucumbers, peas and artichokes. Note that tomatoes, potatoes and capsicums, all originating in the Americas, were not available.

Beetroot was well-known for its beneficial properties. Hippocrates recommended using beet leaves for healing soldiers' wounds, while myth suggests that Aphrodite ate beetroot for beauty. Like modern Greeks, the ancients consumed various wild greens like nettles, dandelions and amaranth greens.

Herbs included basil, rosemary, fennel, dill, sage, oregano, marjoram, spearmint, coriander, chives, bay leaves, thyme and mustard. Capers, sesame seeds and poppy seeds were popular additions to savoury and sweet dishes.

Olive oil and vinegar (but not lemon) were used for dressings. Olives served a versatile role, acting as a common snack eaten fresh or preserved and as an oil, used not only for cooking, but also for lamps and as a carrier oil for perfumes.

A few spices like cinnamon, cumin and pepper were used, especially in later times. Saffron has been used in cooking, medicine and as a dye since prehistoric times. Wall paintings from the 17th century BCE on Santorini Island show young women picking crocus stamens.

Silphium, a plant native to the North African coast, was highly valued in both Greek and Roman times as a seasoning, perfume, aphrodisiac and medicine. It was so prized that it appeared on coins of the Greek colony of Cyrene in modern Libya. Unfortunately, silphium became extinct during Roman times and has not been definitively identified since.

Soups made from mashed vegetables or lentils were common. Carbonised lentils found in Franchthi Cave in southern Greece date back to 11,000 BCE. Popular across the Mediterranean, lentils were considered food for the upper classes in Egypt, but a staple for the poor in Greece. They are also mentioned in the Bible, notably in Genesis, where Esau traded his birthright for a bowl of crimson lentils and a loaf of bread.

Goat and sheep cheese was often enjoyed on its own but could also be included in various dishes. It could be mixed into wheat and barley pancakes, into soups or drinks or served with fish. While rural areas primarily consumed milk, other regions focused on cheese and dairy products like cottage cheese. Butter was rarely used.

Fish, seafood and meat consumption varied by household wealth and location. Fresh and salted fish were popular sources of nutrition. Coastal cities consumed and exported seafood like tuna, swordfish, red mullet, octopus and shellfish. Landlocked areas regarded seafood as a delicacy, often preserved with salt (especially sardines and anchovies). Freshwater fish (e.g., carp, eels) were also widely available.

In the countryside, hunting and trapping provided birds, hares and deer, while snails were also collected. Wealthier landowners had sheep, goats or pigs. In cities, meat was generally expensive, except for pork.

But in general, meat consumption, whether domestic or wild, was less significant than in modern Western diets. Fresh meat and offal were mainly consumed during public or private sacrifices, with pork and beef being the most common, along with lamb and goat. Sausages were more commonly eaten across all social classes. Wealthy individuals occasionally consumed fowl, but quail, pheasant and chicken eggs were eaten more frequently.

Fresh or dried fruits (figs, chestnuts, grapes, raisins, pomegranates, pears, apples, berries and plums), nuts and honey cakes were popular snacks and desserts. Along with honey, grape must was served as a sweetener, often reduced to a molasses-like syrup for preservation.

The Spartan diet was famous for its simplicity and frugality. The main dish was "black soup” made from pigs legs and blood, salt and vinegar. An ancient writer noted, "Elderly men valued it so much that they ate only that, leaving what flesh there was to the younger."

But the black soup was infamous among other Greeks. Someone from Sybaris, a city celebrated for its devotion to luxury and indulgence, joked, "Naturally, Spartans are the bravest men in the world; anyone in their right mind would rather die 10,000 times than take his share of such a miserable diet."

Actually, the Spartan diet was not as bad as it seemed. The soup was served with bread, figs, cheese and occasionally game or fish.

The Greeks used frying pans, large pots, clay ovens and grills to cook their meals.

A key element of modern Greek cuisine is small pieces of meat on skewers, known as souvlaki (small spit). Archaeological evidence and historical writings show that this tradition has deep roots. In scenes of sacrifice, assistants are often seen grilling meat on spits. Historical writings also mention a dish of bread stuffed with meat, akin to today’s souvlaki served with pita bread.

So, here is the answer to my title: souvlaki, yes; Greek salad, no; because there were no tomatoes.

Archestratus, a Greek poet and philosopher, is considered the father of gastronomy and is credited with writing the first cookbook around 320 BCE. He was the first to treat cooking as an art form and is believed to have coined the term gastronomy, meaning ‘rules of the stomach’.

In his humorous poem Life of Luxury, Archestratus provided advice on finding the best food in the Mediterranean and shared secrets of Greek cuisine. The poem highlighted the importance of fish, pulses and wine—staples in both ancient and modern Greek diets.

He presented five golden rules for cooking and eating that remain valuable today:

- Use raw food materials of good quality

- Combine them harmoniously

- Avoid hot sauces and spices

- Prefer lighter sauces to enjoy the meal

- Use spices moderately so as not to interfere with natural flavours.

Archestratus was probably not a full-time cook, as cooks were usually not educated enough to write poetry. Nonetheless, his love for good food and interactions with his cooks and servants are evident in his poem.

So, what did our Massey banquet consist of?

For the entree, we had sourdough and focaccia with olives, rosemary and sea salt flakes, paired with olive oil, vinegar and oregano, and a dip of chickpeas and herbs.

For the main course, we served roasted pork belly marinated in fennel seeds and cinnamon, along with slow-roasted lamb leg seasoned with rosemary, thyme and oregano.

The side dishes included honey-glazed carrots with thyme and walnuts, roasted beetroot with garlic, vinegar and herbs, and a salad of lettuce, cucumber, hazelnuts and figs dressed with pomegranate molasses.

Dessert featured a cheeseboard with goat and other cheeses, accompanied by figs, grapes and assorted nuts. There was also cheesecake flavoured with cinnamon-honey syrup and topped with blackberry jelly.

A selection of Greek wines complemented the meal.

The banquet spread at Wharerata.

At the banquet, there were recitations of poems, as would have occurred in ancient symposia. One was about a well-tempered symposium by the philosopher-poet Xenophanes, which concludes as follows:

Then, when they have made a libation and prayed to be able

to conduct themselves like gentlemen as occasion demands,

they won’t be drunk and disorderly, but they’ll drink as much as they can

and still get home without help – except for a very old man.

We followed those instructions scrupulously, even getting the old man home safely!

Associate Professor Gina Salapata's research revolves around Greek art, archaeology and religion.

Related news

A divine gift: wine drinking in Ancient Greece

Associate Professor Gina Salapata spoke at the Symposium of Gastronomy late last year about the wine-drinking history of the classical Greek symposium.

The Olympics: When athletes were men, nude and Greek

The Olympic Games have a rich history: The inclusiveness of Tokyo will be a world away from their origins in Ancient Greece where men from only the city states of Greece competed nude after prayers and sacrifices