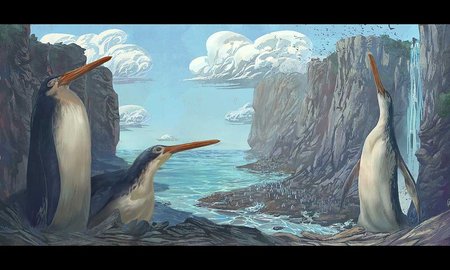

Concept image of the giant extinct penguin Kumimanu fordycei towering over other extinct penguins that were the same size as modern-day emperor penguins. Image credit: Dr Simone Giovanardi.

The fossils were collected from sea-washed boulders in North Otago in the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand by senior author Alan Tennyson of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 2016 and 2017. The fossils were then exposed from within the boulders by Al Manning. They have been identified as being between 59.5 and 55.5 million years old, marking their existence as roughly five to 10 million years after the end-Cretaceous extinction which led to the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs.

To put that in simpler terms, Dr Thomas describes them as really old, even by fossil penguin standards.

Dr Thomas and his former PhD student Dr Simone Giovanardi generated 3D digital replicas of the fossils, which helped the team uncover what these extinct species can tell us about the evolutionary timeline of penguins.

The largest specimen found is the newly discovered giant penguin species Kumimanu fordycei, named after University of Otago’s Professor Emeritus R. Ewan Fordyce. Dr Thomas says being part of this project is particularly significant as Professor Fordyce was his PhD advisor.

“I learned this craft from Professor Fordyce so having that personal connection makes being involved even more special.”

The partial associated skeleton found of this species included the largest humerus (upper-most bone in the wing) ever to be reported, allowing for an estimation of size to sit within the range of 148 kg to 159.7 kg.

Dr Thomas says that the size of Kumimanu fordycei and how early it appears in the history of penguins provides important insight into their evolution.

“In finding this fossil, we’re learning a lot more about the early diversity of these animals. We have found what is essentially a new ceiling for penguin body size, establishing that they got really big really early on, and that maybe evolutionary rates for body size were rapid.”

The discovery of this fossil has provided a strong basis for speculation that a rapid shift towards large body sizes in Paleocene penguins may have been driven by the advantages that bigger bodies provide when trying to retain heat, Dr Thomas says.

“When we start thinking of these finds not as isolated bones but as parts of a whole living animal then a picture begins to form. Large, warm-blooded marine animals living today can dive to great depths. This raises questions about whether Kumimanu fordycei had an ecology that penguins today don’t have, by being able to reach deeper waters and find food that isn’t accessible to living penguins.”

Dr Thomas explains that while not exactly a missing link, it shows a connection between penguins originally being animals that couldn’t tolerate cold water for very long to having a body size expansion that impacted further evolutionary adaptations.

“Penguins are the descendants of flying birds and would’ve looked more like petrels or albatrosses that couldn’t spend as long submerged in marine waters as penguins do today. A classic way to stay warm is to simply be big so that the heat you generate takes longer to be lost from your body into the cold water. What Kumimanu fordycei represents is an insight into the evolutionary history of penguins where there might have been a push to be big to stay warm, perhaps enabling the adaptations we now find in smaller penguins today who can stay warm in cold water without being huge.”

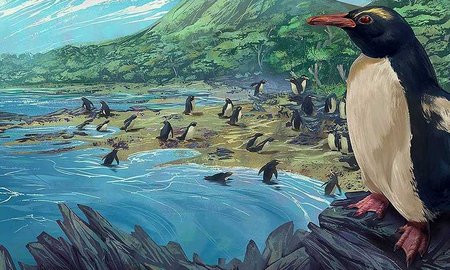

Image credit: Dr Simone Giovanardi.

Reconstructions of newly described fossil penguins (left Kumimanu fordycei, middle Petradyptes stonehousei) compared to a skeleton of the largest living penguin (right, emperor penguin Aptenodytes forsteri). Bones recovered for each species shown in white

The second new species described in the study is Petradyptes stonehousei, named after celebrated polar researcher Dr Bernard Stonehouse, who had been a member of staff at the University of Canterbury. It is represented by five specimens and found to be slightly larger than the extant emperor penguin, scientifically known as Aptenodytes forsteri.

These findings have been reported in a paper published in the Journal of Paleontology, describing the new penguin specimens from the late Paleocene of New Zealand. The collection of fossil evidence continues to provide support for the hypothesis that connects ancient penguin origins to the region of Zealandia, also known as Te Riu-a-Māui, as it remains important to extant penguin diversity.

Dr Thomas says it’s been a real privilege to be part of the team detailing these exciting new discoveries and he is eager to continue this work.

“I’m looking forward to digging more into the fossil history of Zealandia. It is an honour to be able to learn more about the animals that have lived here in the past, especially when they tell us so much about the animals that we share Aotearoa with today.”

Research paper: Ksepka, D., Field, D., Heath, T., Pett, W., Thomas, D., Giovanardi, S., & Tennyson, A. (2023). Largest-known fossil penguin provides insight into the early evolution of sphenisciform body size and flipper anatomy. Journal of Paleontology, 1-20. doi:10.1017/jpa.2022.88

Related news

Giant Waikato penguin: school kids discover new species

A giant fossilised penguin discovered by Hamilton school children has been revealed as a new species by Massey University researchers.

Newly-described fossils reveal an ancient origin for New Zealand penguins.

New Zealand is surrounded by highly productive oceans that attract seabirds from around the world, forming a global hotspot for seabird diversity. Establishing how and when this hotspot formed has been challenged by a lack of fossil discoveries connecting New Zealand's living seabirds to their ancient relatives.

Bird bone streaming

A new website for viewing 3D bird bones aims to make bird bones in museums more accessible for research and teaching.