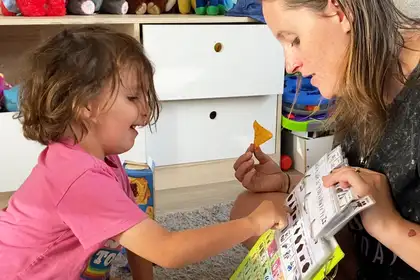

Ali White and son Ryder using a core board.

Sam's research project coached parents in the use of the core board – a communication tool with ‘core vocabulary’ symbols for frequently used concepts like ‘more’ and ‘go’, plus ‘fringe vocabulary’ symbols for specific concepts like people, places, and activities. Children can be taught to communicate by pointing to the symbols.

“It was a year-long project, and I took on six families. The children were three or four years old, so I knew the families would have a lot on their plate. I fully expected to lose at least half of them when they realised how much work it was going to be,” Ms Brydon says.

“But none of the families dropped out of the research, so the project ended up being much bigger than I expected. And the children all had really amazing communication outcomes.”

Ms Brydon’s experience of core boards over the previous 12 years and her review of literature on the subject led her to believe that parents with young families often find the boards too hard to use and give up on them quite quickly.

“They often get provided with a core board and just a brief training session. But supporting children to use an alternative means of communication requires a complex set of skills that aren’t intuitive," she explains.

“So parents might be very enthusiastic when they first get a core board. But after two days of staring at it, not being able to find the words they want, and then having the child throw the board and run off, it ends up being put on a shelf and forgotten about. And the child carries on not being able to communicate.

“My research looked at what support the family needed to use the core board successfully.”

The six children in the study were not using spoken language for a range of reasons, including autism. Ms Brydon organised parental group workshops centred around four sets of skills required to use the core board effectively, followed by coaching in the home.

“All the parents were coming to terms with the realisation that their children weren’t talking. But one positive outcome was that four of the six children did start talking over the year."

“Using augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) has been shown to increase the likelihood that children will develop spoken language if this is possible.”

Using the core board takes both cognitive and physical effort on the part of children, who by the time they encounter the board might have become quite frustrated and found their own way of getting what they want.

“So the parents have to work hard, firstly modelling on the core board, learning where all the symbols are and pointing to them while they’re talking, and they also have to set up opportunities for the child to communicate,” Ms Brydon says.

She says this may mean changing habits which have already been established in the home in the interests of making life easier, such as simply asking the child yes/no questions.

Sam Brydon.

“They have to turn this around and then they have to respond and reinforce any communication attempt. So it’s a really skilled process and parents don’t always know how to do it without support.”

She described the core board as a useful starter tool, relatively cheap compared with a high-tech device, and easy to make and customise. All six families learned to use it well but by the end of the research all agreed it would not do the job long-term as their children got older. Four of the children were talking well enough that it was frustrating for them to use the core board, while the parents of the other two were considering a high-tech communication device with voice output.

“My six families were amazing. It was a very difficult year for all of them – we were in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were family break-ups, illness, funerals, weddings, but they stuck with the research. They were so invested in it working."

“For pre-schoolers, the best people to do any kind of communication therapy are the parents and wider whānau. They are with the children all the time across a range of activities. Professionals are not in a position to provide that level of input.“

Having successfully defended her doctoral thesis, Ms Brydon and her supervisors are now looking for ways to influence the type of support that families receive to implement AAC with their children. This has included meeting with practice leaders within the Ministry of Education, presenting webinars for speech-language therapists through Assistive Technology Alliance New Zealand, and the creation of a two-day workshop for speech-language therapists.

“I love my job. I love the little smile on children’s faces the first time they point to a symbol and get whatever it was they wanted - a look of joy at the realisation they’ve been able to communicate their thoughts,"Ms Brydon says.

Her doctoral research was supervised by Associate Professor Sally Clendon, Dr Elizabeth Doell and Associate Professor Tara McLaughlin at the Institute of Education. Ms Brydon is a member of the Early Years Research Lab at Massey University.

Related news

Speech Language Therapy programme now more widely accessible

Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University is shifting its training programme online from 2024 so it becomes accessible to all students no matter where they live.

Challenges of parenting disabled children during a pandemic

Two Massey researchers are calling for more support from the Ministry of Education and disability support agencies.