Professor Mary Morgan-Richards gets up close and personal with a stick insect

The first male of a New Zealand stick insect species has been discovered, but not where researchers expected.

Massey University’s Professor Mary Morgan-Richards says, “not only was it a surprise for a male of this insect species to turn up, but it was a surprise that it turned up in the United Kingdom.”

“A male stick insect of Acanthoxyla inermis has never been seen before, although the species is common in much of New Zealand. All Acanthoxyla species use parthenogenetics to reproduce, which means that the females lay viable eggs without the need for fertilisation by a male. No males of any Acanthoxyla species have ever been recorded until now,” Professor Morgan-Richards of the School of Agriculture and Environment, says.

“It seems a puzzle why the first male Acanthoxyla should turn up in a small offshoot population on the other side of the world from their native land. It may be that males are to be found in New Zealand, but their rarity means they have yet to come to the notice of researchers in this field.”

The specimen was discovered in the by insect enthusiast, David Fenwick, who found the stick insect on the side of his partner’s car outside in Cornwall, England. Once discovered, Mr Fenwick referred it to fellow enthusiast Paul Brock, to see if he could identify the species. He quickly responded that this might be a ‘eureka moment' where Acanthoxyla has finally produced a male.

Once the find was confirmed, Mr Fenwick attempted to introduce the male to a female, in the hope of a pairing, however there was no evidence of any interaction and the male died the following day, as did the female a few days later.

Massey University Professor Steve Trewick says that quick thinking ensured DNA confirmation could be done in New Zealand.

“As stick insects often do, the male had shed a leg shortly after capture. Fortunately, David immediately placed it in ethanol to preserve it. This leg was forwarded to us in New Zealand, where DNA sequencing was used to confirm with a high level of confidence that it came from an individual whose mother was an Acanthoxyla.”

Professor Morgan-Richards concludes, “the male is likely a mutant, and therefore unlikely to father offspring.”

“A mother has two X-chromosomes, so the production of a son can occur from a mistake during egg formation, when an X-chromosome is lost. The chance of this happening in Acanthoxyla is reduced because many are triploid, with three X-chromosomes.

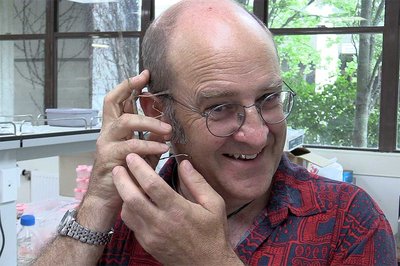

Professor Trewick has his ears inspected by a friendly stick insect

Citizen Science

This find has been declared a win for ‘citizen science’ as the stick insect was found over 18,000km away by keen enthusiasts. Professor Trewick says that around 250–300 reports a year are now being received by the national recorder in the UK, almost exclusively through the online reporting system set up by the Phasmid Study Group.

“What interests us is how can a sex remerge after a species has done away with sex and males altogether. There isn’t a lot of information in this area and it is poorly understood,” Professor Trewick says.

The male was preserved and has been deposited in the national collection at the Natural History Museum, London.

Three species of New Zealand stick insects have now become naturalised in the United Kingdom; the Prickly Stick-insect Acanthoxyla geisovii since Edwardian times, the Unarmed Stick insect Acanthoxyla inermis since the 1920s, and the tea-tree (smooth) Stick-insect Clitarchus hookeri since the 1940s.

The article, Missing Stickman Found: The First Male Of The Parthenogenetic New Zealand Phasmid Genus Acanthoxyla Uvarov, Discovered In The United Kingdom, was published in Atropos.