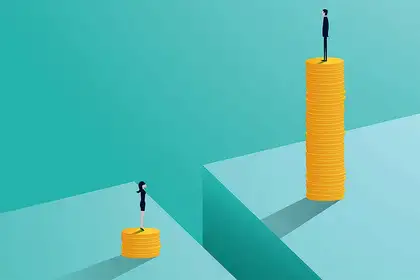

Research shows there is a gender pay gap from the start of women's careers.

Brewing company Lion announced this month it will stop asking job applicants about their current salary at interviews because the question preserves the gender pay gap.

The announcement was made in the same week as data from Statistics New Zealand revealed men earn an average of 9.3 per cent more than women.

Massey Business School’s professor of human resource management Jane Parker says there are a number of recruitment interview questions that can introduce gender-related biases.

Some questions cannot be legally asked, for example, questions about marital status, current employment status, whether the job candidate is pregnant or are planning to start a family.

“In most cases, these questions will be irrelevant to the role for which the candidate is applying,” Professor Parker says. “However, they are sometimes still asked, and if a candidate isn't aware of their illegality and responds to them, this can lead to gender-related biases in recruitment and wider employment practice.”

She says, however, that New Zealand employers may ask a job candidate about current salary.

“Not all jobs are paid equally and fairly, and asking about current salary won't necessarily help close the gap – it could even perpetuate it,” Professor Parker says. “For instance, graduate survey evidence suggests that, even in the same career area, some women earn lower starting salaries than men, and then subsequently ask for lower pay increases than their male counterparts.

“Providing a potential employer with current salary information could reinforce the problem for those women, as well as for any men who didn't negotiate well in their first or subsequent jobs.”

Professor Jane Parker.

Taking a holistic view

Professor Parker says the salary question can be problematic if companies use a candidate's response as a benchmark, and then offer a “top up” that is just enough to persuade them to take the job.

“If a candidate is currently underpaid, this could lead to that person's underpayment in the next job, and they will have to play salary catch-up for years to come,” she says. “Declaring current salary in negotiations may also set a ceiling on what the employer offers, despite the company having a higher budget for the position.”

Professor Parker recommends candidates respond to the salary question by being upfront about salary expectations. They can also ask the company what budget they have in mind for a role, unless a specific pay range is discussed that is below their current earnings. In that case, candidates could mention their existing salary to make the hiring managers aware they aren’t willing to take a pay decrease, she says.

Research also shows men and women are perceived differently when discussing pay.

“Overseas research indicates that when men and women asked for a raise using the same script, both male and female managers liked the man's style and agreed to pay him more, but said the woman was too forceful.

“On the other hand, it's been shown that women who refused to divulge current salary were offered less of a pay rise than women who did disclose. This was attributed to the interviewer's unconscious bias in assuming that the woman did not answer because she earned less.”

Professor Parker says candidates can strengthen their bargaining position by improving their negotiation skills and by knowing what others in similar positions earn. However, pay inequities will only be addressed more widely if organisations act holistically.

“Organisations need to examine the fairness of their pay and other employment practices, and their interactive effects over time,” she says. “That is a key way to identify entrenched or emerging gender-related biases. Elements of an equitable pay strategy should include analysis of appointment panel composition, job requirements and expectations of how pay scales are to be applied within job bands.

“Recent survey research from Massey also indicates that women's greater concentration in certain lower-paying areas of work also adds to the need for a joined-up approach by companies and other parties.”