An Education Review Office (ERO) report found Tokelau's education system needed modernising.

Massey University researchers are helping to modernise education on one of the planet’s remotest places.

Diane Leggett, from the Institute of Education, is leading a major project in her role as Schools Education Leader – Kaihautū Mātauranga Kura, to support the Tokelau Department of Education to transform its education system, bringing digital technology to far-flung coral atolls.

Ms Leggett is part of the Institute’s professional development unit, Tātai Angitu e3@Massey, which has a number of innovative educational development projects underway in New Zealand and abroad.

She has visited the three Massey education field facilitators (Sheree Drummond, Akaiti Maoati and Elaine Lameta), twice yearly since the project began in November 2014. They are based on Tokelau’s three atolls – Fakaofo, Nukunonu, and Atafu – where they are working with teachers in the second phase of the project to implement policy and curriculum changes to bring teaching and learning on the tiny Pacific Island nation (population 1500) into the 21st century. There are approximately 130 pupils per atoll, with one school on each for children of all levels.

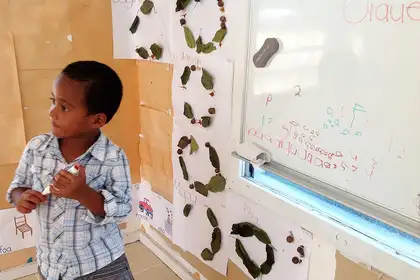

Year 7 and 8 pupils working on new laptops.

Tokelau education needs modernising: ERO

A 2013 Education Review Office (ERO) report found that the education system in Tokelau (a dependent territory of New Zealand) was based on models, ideas, materials and assessment methods of 1960s New Zealand, with little understanding of the value and role of early childhood education. Tokelau’s system also lacked effective teacher training, professional development and mentoring, as well as governance structures and processes, the report said.

The Massey team was contracted to work with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade to address the ERO’s recommendations.

Phase one of the programme developed an education plan formulated following extensive consultation with Tokelau’s policy makers, school principals and teachers as well as pupils, parents and Taupulega (Council of Elders). The plan incorporates traditional values, knowledge and language of Tokelau culture, with transition to the new system by 2019.

Educational priorities also address vocational training to meet the need of the nation’s workforce, from machinery servicing to government jobs in health and education.

Co-construction is the key. “We’re not imposing any models – we work alongside our Tokelau counterparts,” says Ms Leggett. “There’s a lot of goodwill.”

A teacher inquiry model focussed on identifying and meeting students learning needs has replaced the traditional rote learning experienced by children. New books (in Tokelau and English) as well as innovative teaching practice alongside digital technologies are among the ways Tokelau’s youngsters – from early childhood through to secondary level – are benefitting.

Teachers on the island are already reporting improvements, two years into the project. Apaenisa Leano, a secondary level science teacher who has taught in Tokelau for the past two of 14 years in teaching, says his students are “more engaged when I use many different ways for learning to happen.

“For example, we did a science field trip on the reef. We used videos and group learning situations where the children ask and answer their own questions. Before I had this professional development, I planned to cover the curriculum. Now I plan so I cater for all my students. I use what I know about their achievement and abilities to decide what I need to teach and what level I need to teach them at.”

A school principal has observed changes in teachers’ conversations, noting; “Teachers talk about children and their learning where once upon a time they talked mainly about behaviour.”

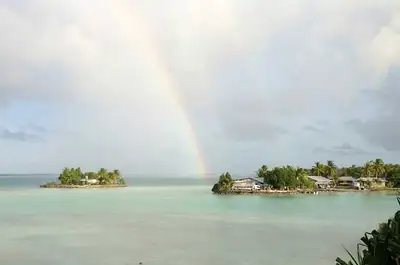

Rainbow over remote Tokelau.

Education to strengthen Tokelau’s culture and traditions

While the prospect of living on a remote tropical paradise sounds alluring, it can be a challenging environment for outsiders not used to extremes. Tokelau is the only nation in the world that runs 100 per cent on solar power, but the aridity means inhabitants rely on imported foods to supplement locally grown coconuts, bananas and breadfruit. They also raise pigs and chickens, and catch fish in the lagoons. Atolls are frequently battered by cyclones and temperatures soar to over 40 degCel.

Satellite access to the Internet on Tokelau makes connection expensive. However, Massey’s education advisors have established virtual online learning communities for teachers to be able to communicate with mentors in New Zealand to discuss ideas.

“The project is being undertaken at a critical time for the island nation, which is under threat from rising sea levels caused by climate change. While many Tokelauans have migrated to New Zealand, Australia and other parts of the world, creating educational resources that will ensure the Tokelau language and culture can be preserved for future generations is a central part of the project,” Ms Leggett says.

She will next travel to Tokelau to oversee a series of education workshops in July, making the six-hour boat trips between atolls.

A 26-hour boat trip from Apia, Samoa over rough seas aboard the Mataliki, a purpose built boat that carries passengers and cargo, is the only way to reach Tokelau’s coral atolls. It is too rough to read or use a computer, she says, so she tries to sleep on the upper deck.

Barry Potter, another Massey facilitator who visits schools on the atolls, says a key part of his role is immersion in the Tokelau culture and fitting into the rhythms of atoll life, which is based around weddings, funerals, kilikiti (cricket), national flag day, teacher day and dances.

“Other interruptions include getting to and leaving the atoll on the boat which is an unpredictable exercise,” he says. “The boat seldom arrives or leaves on the day and time it is scheduled. When the weather is too rough for the boat to get to the atolls, supplies run short. So when it does arrive, everyone rushes to get the fresh food, and if you’re too late you miss out!”

Very few people ever get to visit Tokelau. Due to its isolation it is not a tourist destination, but Ms Leggett says the people are very welcoming and friendly, and that “looking out at a sunset over the lagoon, it must be one of the most beautiful places in the world.”

Tātai Angitu translates from Māori as “linking opportunities” and e3 denotes its three core strands: education, efficacy and enterprise.