Just days into the new political year, and the Prime Minister’s attempt to focus on anything that is not the ACT party’s proposed Treaty Principles legislation is not going well.

ACT leader David Seymour is on record as having said that the legislation stems from his party’s objection to people being treated differently on the basis of race. Mr Seymour is quite right that Māori are often treated differently, although he appears not to be aware of the extent to which this has generally not been to their benefit.

There is no shortage of evidence, if you can be bothered looking for it. Here are just a few unrelated but far from unusual data points.

A brief history of Aotearoa New Zealand

In 1848, the Crown paid £2,000 for the purchase of 20 million acres (nearly a third of the country’s land mass) of Ngāi Tahu land. Henry Kemp, the Governor’s Native Secretary, promised that ‘ample reserves’ would be set aside for Ngāi Tahu: just 6,359 acres (or 0.031 per cent of the total Kemp Purchase) were eventually handed back to the iwi.

In 1892, the West Coast Settlement Reserves Act gave the Public Trustee the authority to lease land owned by Māori to Pākehā farmers in perpetuity. Māori landowners could not hold these leases or set rents, but they could be charged survey fees, Crown and Native Land rates, the costs for bush-felling, a 7.5% commission paid to the Public Trustee, land taxes, interest on overdrafts, and the costs associated with advertising leases, fencing, draining and building roads on land they owned but might never be able to farm themselves. In 2023, those perpetual leases are still locking Māori off land they own.

In 1899, despite repeated offers of service from te ao Māori, Māori were officially excluded from military service in the South African war, the first overseas conflict in which the New Zealand military played a role. Some individual Māori did serve but did so under European names.

In December 1921, the local priest at the Ōkato parish wrote to the head of the Roman Catholic Church to explain that while ‘the Whites’ would be coming along to the traditional midnight mass on Christmas eve, Ōkato’s Māori parishioners were expected to attend a separate mass.

In 1922, Hori Teira sold 98 acres of land to my great-grandmother for £2,947 (which is just a bit more than Ngāi Tahu received for the Kemp Purchase). It is not clear that he ever received this money, because the Native Land Act 1909 gave the District Māori Land Boards the right to keep proceeds from the sale of land if a Board considered a Māori landowner incapable of controlling money thus gained – and the archival recordsuggests that this is what happened to Hori Teira.

In 1951, Mrs Louie Okeroa went to the Marine Department in New Plymouth to sign and pay for a lease on 18 acres of land her whānau had farmed at the end of the Cape Egmont Road since 1887. The department’s officials, who were ‘not very enthusiastic to lease [the section] to a Maori’, refused to allow Mrs Okeroa to sign and pay for the lease. Shortly thereafter, the land was sold to a neighbouring Pākehā farmer.

And so on, and on, and on.

Professor Richard Shaw.

Yeah but nah

There are those, of course, who will argue that all of this sort of stuff happened in the past and should have no bearing on what is going on now. These days, we’re all equal. This position both begs a question and ignores a reality. The question is: in what year does ‘the past’ end? What are the temporal bookends to this conversation? Are we just counting the last year? The last five? The last fifteen? What is in scope?

The reality is that history has consequences, some of which can last for a very long time indeed. Ask the Irish, many of whom were living in such poverty, centuries after English imperialists confiscated their land, that they sailed here in search of a life that would not be lived in the eternal shadow of colonisation. Some of those Irish, my ancestors amongst them, settled on land that had been confiscated from Taranaki iwi in 1865. Most of that land remains confiscated. Bluntly, the consequences of 1865 continue to be felt today, on both sides of the raupatu line. History never goes away.

So by all means, advocate a national conversation about equality of treatment but please ensure that it is informed by our actual history rather than the fantasy one in which some believe we’re all treated equally.

What’s really going on

It would be a good thing, too, if what is presently being framed as an issue for Māori was seen for what it really is – a significant challenge to the constitutional consensus regarding Te Tiriti o Waitangi that has emerged over recent decades through the actions of citizens, the courts, the parliament and the executive branch. That Te Tiriti is a cornerstone of our constitution is now a settled matter. One of the clearest and most authoritative statements to this effect is in the Cabinet Manual. The ‘primary authority on the conduct of Cabinet government in New Zealand’, and itself part of our constitutional arrangements, the Manual is quite clear that ‘the Treaty of Waitangi is regarded as a founding document of government in New Zealand.’

In other words, the ACT’s Treaty Principles legislation is not just about Māori. It does, and should, concern all of us, because it has to do with the way in which we structure and apportion the power of governing institutions. This issue is collective, not something that can be passed off as a ‘Māori issue’. This is on all of us. The Prime Minister will not be able to dodge this for very much longer. Neither will we. Māori, New Zealand European, Pākehā, new migrant or someone from old settler stock – we all share a political genealogy that reaches back to Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Shortly, we may all be faced with a choice: to reaffirm that shared political heritage or erase the past in an act of selective historical amnesia.

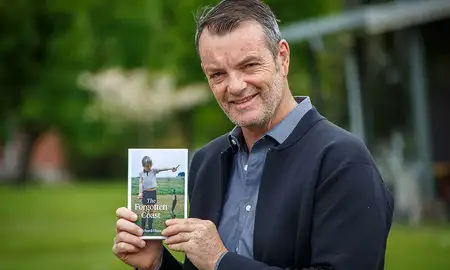

Professor Richard Shaw is a professor of politics in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. He is a regular commentator on political issues and has recently written his latest book The Unsettled which explores historical and emotional territories of New Zealanders coming to terms with the ongoing aftermath of the New Zealand Wars.

Related news

Opinion: The politics of ‘wide purposes’ – how Norman Kirk still speaks to 21st century New Zealand

By Professor Richard Shaw.

Memoir explores racism, the Catholic church, and fathers

Professor Richard Shaw has launched his memoir 'The Forgotten Coast', an examination of colonial privilege, his family's Catholicism and his relationship with his father.

The complicated world of online misinformation and disinformation

In episode three of Conversations That Count - Ngā Kōrero Whai Take, our guests Professor Richard Shaw and Jess Brenton-Shaw dive into this complicated issue.