Image credit: Public Domain Pictures, via Pixabay.

Sir Keir Starmer’s United Kingdom Labour Party has just won a parliamentary majority for the ages. The electoral coalition, assembled in 2019 by former Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson, collapsed over the weekend, as Tory bastion after Tory bastion fell to Starmer’s Labour (or to Ed Davie’s Liberal Democrats) in a result that brought the curtain down on 14 years of tumultuous Conservative rule and ended the careers of a number of senior Tory MPs.

At first glance, it is heady stuff. Look a little closer, however – say, from a New Zealand point of view, where under proportional representation parliamentary elections are determined by political parties’ share of the national vote rather than individual constituency contests – and a very different picture emerges.

Bluntly, the UK election is a striking example of the ways in which plurality (or First Past the Post (FPP)) electoral systems distort the conversion of voters’ preferences into parliamentary representation.

Starmer’s Labour won 412 (or 63 per cent) of the 650 seats up for grabs in the House of Commons – but it did so on the basis of just 33.8 per cent of the vote. Put another way, two thirds of voters did not vote for a party which now has control of the Treasury benches and a manufactured parliamentary majority of 86 seats. Add to that a turnout rate of just 60 per cent of eligible voters (in 59 constituencies turnout dropped beneath 50 per cent), the lowest since 2001, and it becomes clear that an overwhelming majority of potential voters in the UK did not vote for their new government.

It may be true that decisions are made by the people who turn up, but Labour is now governing in a demoralised democracy, and Starmer will be mindful – in the context of global concerns about the parlous state of liberal democracies – of Lord Hailsham’s warning about behaving like an ‘elected dictatorship’.

The Liberal Democrats – ironically, amongst the strongest advocates in the UK for the adoption of proportional representation – also benefited from the peculiarities of FPP. Ed Davies’ party won fewer votes than Reform UK (12.2 per cent against 14.3 per cent) but picked up 71 (11 per cent) of the seats on offer – nearly 15 times the number Nigel Farage’s party won. They may be the third biggest party in the Commons but they trail Reform for support out there in the wider national constituency.

Professor Richard Shaw

Unlike the experience at the last UK election in 2019, however, when the situation was reversed, this time round the parties on the right came off second best under the electoral arrangements. The Tories secured 23.7 per cent of the vote but held on to just 121 (19 per cent) of seats in the Commons. Just as the UK’s voting system disproportionately rewarded Labour and the Lib Dems, it punished the Tories, who won around two thirds as many votes as Labour but just a third the proportion of Starmer’s party’s seats.

And in what, over the long haul, may well prove to be the most consequential result of the night, Nigel Farage’s extremist Reform UK – which is not a political party at all but a limited liability company – took five seats on the strength of 14.3 per cent of the vote (and came second in dozens more). That is, Farage’s vehicle got more than half the Tory vote and comfortably outperformed the Lib Dems on vote share but picked up just 0.8 per cent of the Commons seats.

What might all of this look like had the election had been held under New Zealand’s electoral rules, which distribute parliamentary seats in proportion to a party’s share of the total popular vote?

Roughly speaking (and putting aside messy questions about thresholds, coat-tailing rules and overhangs), Labour would have won 218 seats (not 412); the Conservatives would have 154 seats (33 more than they actually got); Reform UK would be sitting in 93 (and not 5) seats; and the Lib Dems would have 79 spots.

In this parallel word there is no Labour landslide. In fact, there is no parliamentary majority for Starmer and, quite possibly, no Labour government. Starmer cannot get to 326 even with the support of the Lib Dems. Neither does a putative (and unlikely) Tory/Reform coalition get over the line – what exists, instead, is a hung parliament and a gnarly process of government formation ahead.

None of this applies in reality, of course, but as a thought experiment it does illuminate some of the consequences of FFP electoral systems that go missing if the analysis of the election stops at the headline figures. For one thing, the UK electorate is extraordinarily volatile: the swing from the Conservatives to Labour (and away from the Tories in general) in the space of just five years is spectacular, and Starmer will be clear that many of the votes he won over the weekend are essentially ‘borrowed’ ones. He has them on loan and will need to deliver, quickly, if he is to hold them.

The results also speak to an ongoing realignment in the British political system. One dimension of this is the emergence of third parties as electoral (if not yet, because of the FPP, parliamentary) forces. Between them, the Labour and Conservatives parties won a miserable 57.5 per cent of the vote. They may have been rewarded with 82 per cent of all Commons seats, but tectonic forces are at work in the party system – especially on the right and extreme right, where support for Reform and the loss of Tory moderates like Penny Mordant and Grant Shapps may open the way for a new party leader (although it won’t be Liz Truss 2.0) to take the Tories further to the right.

Paradoxically, too, FPP has given Starmer both a victory and a problem. The size of the parliamentary majority he now commands comes with challenges for the incoming Prime Minister and his senior people. There are only so many cabinet roles to go around and so many positions on legislative committees to fill. One of the traditional powers of a Prime Minister in a Westminster system is the ability to allocate portfolios: in Starmer’s case, there will be a lot of people left holding out their hands, and five years on the government’s backbenches is a long time for ambitious people to wait. There will be many idle hands.

There is a great deal more to be parsed from recent events in Westminster (including the ramifications of the Scottish National Party’s poor performance for the prospects of Scottish independence). For now, though, while his party has just won power in a landslide, Sir Keir Starmer will be hoping he has not been left standing on a sandcastle.

Professor Richard Shaw is a Professor of politics in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Related news

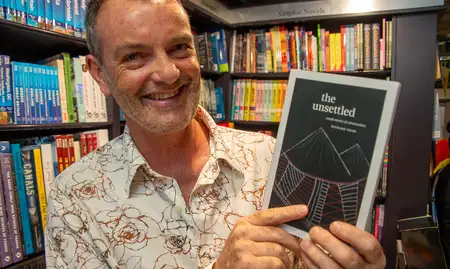

The Unsettled: Small stories of colonisation

Professor Richard Shaw’s latest book explores the historical and emotional territories of New Zealanders coming to terms with the ongoing aftermath of the New Zealand Wars.

Opinion: Let’s talk about equality – and the constitution

By Professor Richard Shaw

Opinion: The politics of ‘wide purposes’ – how Norman Kirk still speaks to 21st century New Zealand

By Professor Richard Shaw

Memoir explores racism, the Catholic church, and fathers

Professor Richard Shaw has launched his memoir 'The Forgotten Coast', an examination of colonial privilege, his family's Catholicism and his relationship with his father.