Professor Mohan Dutta is Dean's Chair Professor of Communication. He is the Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), developing culturally-centered, community-based projects of social change, advocacy, and ac

By Professor Mohan Dutta.

One of the mainstream liberal responses to the #Convoy22NZ protests are the calls for dialogue. These calls, emerging from a wide array of mainstream sources, including the Human Rights Commissioner, suggest that dialogue promotes social cohesion. They build upon the idea of dialogue to suggest a middle ground that is to be achieved through listening to all communities, preventing polarisation.

Implicit in this dominant framing is the “both sides” logic, with dialogue serving as a resource for developing mutual understanding between the two differing sides.

But what exactly is the middle ground when democracies are faced with viral disinformation campaigns, organised by powerful political and economic interests, leveraging the profiteering logics of platform capitalism?

What exactly are the registers of dialogue when dealing with a protest that is propelled and co-opted by disinformation and hate, deeply rooted in the ideological apparatus of white supremacy seeking to seed chaos and capture power by undermining democratic institutions? What message does the performance of dialogue with campaigns fed by white supremacy send out to Māori, Pacific, and ethnic communities who are the targets of the hate perpetuated by the far-right? In the backdrop of the Christchurch terror attack, what message does dialogue with a protest fuelled by white supremacy send to Muslims in Aotearoa New Zealand who continue to grapple with the trauma of the violence?

Antithetical to the idea of building social cohesion, superficial attempts at listening and dialogue mainstream the far-right, giving the far-right credibility and the opportunity to grow. The irony is profound that the reference to “listening to communities—all communities” in the calls for dialogue covering the statements by the Human Rights Commissioner refer to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Christchurch attack targeting Muslims and migrants.

Situate this irony in the backdrop of the voices of Muslims in Aotearoa New Zealand, who continue to highlight the erasure of Muslim voices and the unresponsiveness of the Crown structures to Muslim voices documenting and raising concerns about Islamophobic hate. In an Official Information Act response to Christchurch youth advocate Josiah Tualamali’i, Crown Law, the organisation responsible for drafting the terms of the Royal Commission inquiry, stated “in drafting the terms of reference Crown Law did not consult with Muslim community leaders, and or victims of the attacks.”

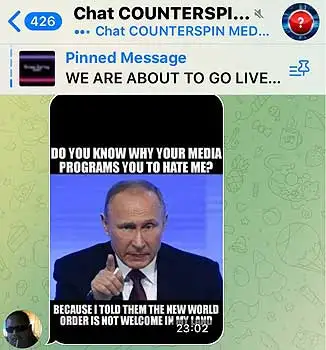

An image from the Counterspin Media channel taken from the Debunking Conspiracies Aotearoa Twitter account.

Whiteness and dialogue

The uncritical and celebratory view of dialogue as a human right reflects the whiteness of the mainstream approaches to dialogue, upholding as universal the values of the dominant white culture. Instead of building registers for justice that are attentive to the inequalities that constitute communicative spaces, the upholding of facile dialogue as panacea reproduces and magnifies the disinformation and hate perpetuated by white supremacists.

The protest is shaped by disinformation and hate that is being seeded and circulated by right-wing white supremacist hate infrastructures, connected to and imported from the Trump-aligned fascist communicative infrastructures in the United States. Note the convergence in strategies between #Convoy22NZ and the Capitol riots calling for citizen-led arrests of policymakers, jailing them, and carrying out executions.

Counterspin media, a platform that has been covering the protests and feeding protestors with disinformation, is a key media resource in the mobilisation of the protest.

As observed by digital activist Byron Clark, who spent a week at Massey’s Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) last year as an Activist-in-residence, co-writing a white paper on resisting digital hate, Counterspin Media Limited is streamed on the Steve Bannon-led GTV network and is a key resource in organising and circulating disinformation and hate here in Aotearoa New Zealand. In spite of multiple early warning signs about the presence of this hate infrastructure, the Crown has largely been unresponsive, and digital platforms have continued to profit from the virality of hate content. This is particularly disappointing in the backdrop of the rhetoric of the Christchurch Call.

The host of the platform, Kelvyn Alp, has actively promoted disinformation and hate propaganda. He has called for the #Convoy22 protestors to storm parliament and arrest Members of Parliament, making multiple references to killing them. On Counterspin Media, he states on March 2, "Can you imagine if a few boys brought out of their boot a few AK-47s? Those muppets would have run for the hills. That's the problem. You disarm a population under a false flag so they can then come and eviscerate you."

He is joined by other white supremacists Brett Power, Philip Arps, Damien De Ment, and the white nationalist group Action Zealandia.

Consider the Christchurch conspiracy video circulated by Counterspin Media amidst the protest coverage claiming the falsehood that the Christchurch terrorist attack was a false flag.

White supremacists systematically target indigenous and other minority communities with disinformation and hate propaganda. White supremacist propaganda targeted at black, Indigenous people of colour (BIPOC) communities seeds chaos and catalyses the multiplication of disinformation and hate. Consider for instance the role of white supremacists in the US in co-opting #BlackLivesMatter protests and organising violence.

These propaganda infrastructures operate largely on digital platforms such as Telegram, Facebook and Twitter.

Simultaneously, they create and craft spectacles that draw mainstream media attention, further perpetuating the disinformation. The production of the spectacle therefore is a key strategy in placing onto the mainstream the discursive registers for disinformation and hate.

Communicative inequality and just dialogues at the margins

Communication is constituted by colonial, raced, classed, gendered inequalities.

Calls for dialogue that erase these inequalities uphold the power and control of the coloniser. A framework of dialogue rooted in justice recognises these communicative inequalities and seeks to build infrastructures for the voices of the margins.

Just dialogues would need to begin with developing culture-centered pedagogies for communities at the margins that challenge the disinformation and hate, created and led by communities at the margins.

Across digital platforms, I have witnessed a number of anti-racist Māori activists and leaders such as Tame Iti, Marise Lant, and Matthew Tukaki who have taken the leadership in countering the disinformation catalysing the protests. They have been doing this work continually, engaging communities in critical conversations.

They have simultaneously been doing the work of building critical pedagogy on an ongoing basis, exposing the underlying ideology of white supremacist hate driving the protests.

Respecting the commitments of Te Tiriti would put Māori leadership at the heart of any strategy of dialogue and social cohesion.

Respecting the voices of Muslims in Aotearoa New Zealand who have in recent years borne disproportionately the burden of violence emerging from white supremacy would centre the voices of Muslims, particularly Muslims at the intersectional margins in building solutions for social cohesion.

Moreover, the infrastructures for listening to the voices of the raced, classed, colonial margins in the context of the #Convoy22NZ protest would attend to the ways in which the whiteness of the Crown’s COVID-19 response has produced interpenetrating forms of marginalisation, seeking to build solutions that address the economic disenfranchisement resulting from policies.

Partnering with and supporting the leadership of communities at the margins as the drivers of solutions is going to be vital to countering the Trumpian infrastructure of disinformation and hate that has planted its roots in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Professor Mohan Dutta is Dean's Chair Professor of Communication. He is the Director of the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE), developing culturally-centered, community-based projects of social change, advocacy, and activism that articulate health as a human right.