A screenshot of a video from the swearing in of Labour MP Guarav Sharma on Wednesday 25 November.

By Professor Mohan Dutta.

Language is deeply political and constituted in terrains of power. The politics of language is evident in the struggles for Te Reo Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand.

When I witnessed Labour MP Dr Gaurav Sharma, of Indian origin, take his oath in Te Reo, I was joyful to see the possibilities of solidarity with the struggles of tangata whenua articulated in the gesture.

The MP then proceeded to take his oath in Sanskrit.

While the MP’s use of Sanskrit to take the oath may be seen as another triumph for multiculturalism in New Zealand politics, the gesture raises vital questions to ponder upon, particularly in the context of the hegemony of the majoritarian politics of hate in contemporary India.

This politics of hate that underlies the governing structure of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India is built on the revitalisation of Sanskrit, the turn to Hindu knowledge claims, the erasure of diverse cultural claims, and the active attacks on India’s oppressed caste and minority communities.

Sanskrit is largely a scriptural language that is used by caste Brahmins in India, reflective of and imbricated in India’s caste structure. Used historically by Brahmins to perform sacred rituals, Sanskrit was held up by a politics of caste-based gatekeeping.

Since its ascendance to power, the BJP has deployed Sanskrit as an instrument of marginalisation. Sanskritisation has served as a vital resource in the saffronisation (right-wing policies which impose a Hindu nationalist agenda) of the nation.

The caste politics of Sanskrit is particularly salient in the backdrop of the ongoing violence on outcaste (dalit) communities under the BJP regime.

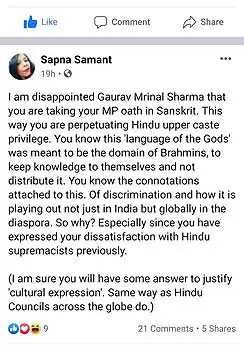

The Indian origin activist Dr Sapna Samant voiced on Facebook how the act of oath-taking in Sanskrit by a Labor MP lends credence to the Hindutva forces in India.

In response to the post, Dr Sharma untagged himself and unfriended her.

A Facebook post by Dr Sapna Samant.

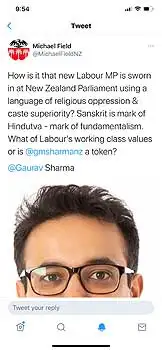

When similar questions were raised by the New Zealand journalist Michael Field, the army of trolls that props up the digital infrastructure of hate underlying the hegemony of India’s ruling right-wing BJP catalysed its attack on him. The story was also picked up by Indian Weekender, accusing Michael of ignorance and bigotry.

Indeed as suggested by Dr Samant, Dr Sharma’s utterance of the oath in Sanskrit gave great succour to the Hindu right, with the digital networks of hate picking up and circulating his performance. At the same time, anyone asking critical questions was systematically targeted, reflective of the online army of hate that holds up Hindutva.

When in solidarity with Michael Field, I tweeted about the Brahminical hegemony of Sanskrit, and its complicity in the politics of caste, I quickly became the target of the Hindutva troll army.

A tweet by journalist Michael Field.

One tweet was all it took for an entire machinery of hate to be unleashed on me, reflective of the digital discursive climate in India.

Other Indian origin minority activists pointing to the link between the use of Sanskrit and the organised politics of hate in India have been subject to similar attacks.

The infrastructure of hate invoked by some necessary critical questions points precisely to the problematic hate politics that constitutes the cultural space in India. It also points to the ways in which uncritical multiculturalism can end up mobilising hate politics.

Tweet by Professor Mohan Dutta.

Superficial appeals to multiculturalism that obfuscate the interplays of power underlying these hate politics propels further the politics of hate. Taking an oath in Sanskrit, attending a ceremony at a Hindu temple, wearing a tika (a red mark on the forehead) or wearing a saffron shawl can all appear as markers of multicultural openness. They can, in a specific context, signal inclusiveness. In other contexts, these same symbols and cultural resources can work to signal a politics of violence and erasure.

Indian origin politicians in the diaspora have vital roles to play in nurturing inclusive diaspora. That work requires careful reading of cultural symbols, deep reflexivity of the interplays of power in the circulation of symbols, and an openness to having difficult conversations.

The spirit of the Christchurch Call seeks to limit violent extremist content online. One important step toward that change is for politicians, especially politicians from parties with progressive agendas, to be mindful of how their expressions of multiculturalism might be taken up by right wing forces of hate.

Such mindfulness can only come about through difficult dialogues. Centering power in our conversations on culture is an important starting point to building multicultural spaces that are inviting and open.

Tweet from an internet troll.