Dr Laura Jean McKay with her prize-winning novel about a pandemic (photo/Dr Kyra Clarke)

Dr Laura Jean McKay had just finished editing a novel about a viral pandemic and left behind raging bush fires in her homeland to take up a teaching job here, when life began imitating art. Cue COVID-19. Titled The Animals in That Country, her book has just taken out Australia’s most valuable literary prize.

Now teaching creative writing at Massey’s Manawatū campus, Dr McKay is coming to grips with the “life-changing” success of winning the AU$100,000 Victorian Prize for Literature, as well as the AU$25,000 Fiction Award, announced in early February.

Her novel, in which a rogue virus gives infected humans the ability to understand animals, was up against shortlisted celebrated writers such as Richard Flanagan. While she defines the book – her first published novel – as “speculative fiction”, aspects of the pandemic theme turned out to be scarily accurate.

As bush fires burned out of control in New South Wales and Victoria at the end of 2019, the first cases of coronavirus were emerging in China as she was doing final edits prior to publication with Scribe. She briefly returned to Australia to make an audio recording of the book. It was just before lockdown. “There I was, reading out scenes of people locking down, wearing masks etc. Then I would go out to the supermarket in Sydney and people were wearing masks – there were these weird replications!”

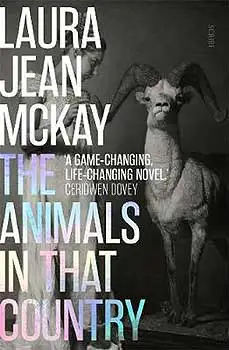

Book cover

Impressively prescient as this may seem, Dr McKay declines oracle status, saying “any pandemic follows a trajectory. I’d been an aid worker during the SARS virus, so I knew the pattern.”

Set in Australia in the near future (without naming the country), the ambitiously imaginative work centres around Jean, a middle-aged ranger in the midst of divorce who likes her smokes and booze and prefers the company of non-human creatures. Animal characters include a dingo named Sue as well as a cast of birds, insects, mice, wallabies, a koala and a whale.

“The main idea was that we all have connections to other animals whether we like animals or not…yet we sort of see ourselves as superior because we have language,” she says. Her novel explores “what would happen if we took away that language barrier. What would happen if we could finally understand what they were saying?

“In the novel it turns out they’re not saying ‘I ruve you’ – they’ve got their own things going on.”

While she is not the first novelist who gives voice to animal characters (George Orwell’s 1945 allegory Animal Farm is a classic), she was worried at the reaction when she’d tell people her PhD was in literary animal studies. “People would laugh – it sounded ridiculous to them.”

However, she found courage and inspiration from a legacy of writers – including George Orwell, Eva Hornung (Dog Boy) and Witi Ihimaera (Whale Rider) – and publishers who “believed in the book and fought for it.”

Her research included living in a wildlife park in Northern Territory for months, speaking to rangers and spending time watching wild and captive animals. Celebrating the diversity of animal biology and bodies, and imaging how they experience reality, is another dimension of the book. “Take the extraordinary experience of perceiving the world sonically as a bat does. What does that do to your world view when you don’t prioritise vision and language as we do? How does that change everything?”

Laura at the Manawatū campus

Kafka-esque crisis

A frightening encounter with the animal world has shaped her life and writing, heightening an awareness of the fragile boundaries between humans and non-humans. She attended a writers’ festival in Bali in 2013, was bitten by a mosquito and contracted the rare disease chikungunya – "health workers describe it as being like dengue on crack," she told Australia’s ABC News.

Symptoms included extreme fever, peeling skin and arthritis that made her so weak she could just crawl up the stairs to her writing desk, adding, “it’s disgusting, but leaving a trail of skin.”

Enduring Kafka-esque moments, she become so delirious with fever that; “at one point I thought I must be turning into a mosquito – I thought that’s the only explanation for what’s happening to me.”

Echoing Franz Kafka’s 1915 novella The Metamorphosis (in which the main character awakes one morning to find himself transformed into a giant insect), she wrote a story about the experience. Her latest work is also “infected” by the illness, which took two years to recover from. Amazingly, she had just begun her PhD and was able to work on this intermittently as her health slowly improved.

Always an avid reader, Dr McKay says her writing reflects her background in humanitarian work and her interest in researching post-colonialism and de-colonialism. A deep awareness of power structures is at the essence of her writing. Her first book, Holiday in Cambodia (a short story collection) was published in 2016.

Was she destined to be a writer? Her mum and aunties were librarians. “There were books everywhere – everybody read all the time.”

She and her mother and brother lived with her aunt Nola who had a rural library bus in Gippsland, Victoria. Her father Ross, who died just before she was born, was a poet and she feels that growing up with his work – published posthumously by her mother – is also part of her legacy.

Melbourne to Manawatū

Coming to New Zealand with her Kiwi partner Tom Doig, also an author, Dr McKay says she is excited by the energy and support of the creative writing department at Massey. It is, she says, “filled with active writers who are passionate about the craft, who are producing amazing works all the time and who are dedicated to the programme – it’s really exciting.”

She is currently teaching first year courses in Creative Writing and Creative Communication as part of the Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Communication programmes and is excited about the launch of a new Eco-Fiction and Non-Fiction paper she is coordinating with Associate Professor Ingrid Horrocks in Semester Two.

Having lived in her imagined pandemic for some time, she says the real pandemic is much more serious and devastating and is saddened to see the continued progression of COVID-19 globally and the suffering of so many. She left Australia in a trail of smoke and flames and an emerging global virus. “Now I’m pretty much in the safest place in the world in terms of Covid response, and everyday I’m grateful for that. The way the government responded, the way the people have responded – it’s so inspiring.”

For more information on studying Creative Writing in Massey’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences, click here.