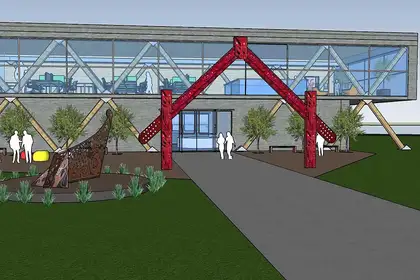

Planning students' design for a Māori tertiary centre in Masterton's Eastside.

Turning graffiti into public art and creating a Māori university are among the bold ideas of a class of Massey University planning students who collaborated with a local community and council to revitalise a low socio-economic Masterton suburb.

Masterton East – also known as the Eastside or Cameron Block – is a social housing area, a bit off the radar and neglected. Its population of around 3500 makes up around 15 per cent of Masterton’s population and just over 30 per cent are Māori (Rangitane and Ngāti Kahungunu).

The class of 14 students worked with the Masterton District Council, Connecting Communities Wairarapa and Masterton Eastside Community Group on the Community-led Development Design for Masterton East. In their final report the students, in their fourth and final year of the Bachelor of Resource and Environmental Planning degree, provided a professional portfolio detailing their engagement process, research and designs for revamped or new buildings, walkways, community gardens, pedestrian underpass, Māori art for urban settings and traffic solutions.

They explored three key themes: education (what linkages can be made between the suburb’s three schools and the wider community and how might opportunities and spaces for adult education be incorporated); community hub (what is the best location for the community centre and how best to foster links with sports and other groups); and open spaces and gateways (how to incorporate green spaces into the neighbourhood).

Their work included visits to Masterton for stakeholder and collaborative community workshops with everyone from teens to school principals, police, community leaders, older residents and business owners to develop a shared understanding of the values and aspirations of the key stakeholders and their vision for the future. They undertook community-led analysis of the issues and needs of the community before coming up with designs – based on Māori concepts of ahi ka (nurturing home); taiao (human connection to the natural world); whakapapa (genealogy); mana (authority, status); tohu (to preserve); and mahi toi (art work) – which they presented to the council officials and community members in October.

Design for giant spraycan sculptures for a skatepark where graffiti is seen as art for younger residents of Eastside.

Graffiti as art, not crime

In a group interview about their project four of the students, Phoebe Watson, Hannah Van Haren-Giles, Alicia Todd and Josh Knowles, said one of their main priorities was to cater for the needs of the younger demographic from teens to early 20s.

“The challenge was to find stuff in between a kids’ playground and walkways for the elderly,” says Phoebe.

This meant they had to take on board a range of sometimes conflicting ideas from the community and find solutions that would work. Younger residents indicated they wanted the local skatepark to be lit so they didn’t have to leave when the sun goes down.

The students also came up with a design for an associated series of landmark concrete pillars shaped like spray paint cans. “We felt these spaces would encourage community graffiti as a positive thing – in a way that’s interpreted more as art than graffiti.”

Initially, the idea of a skatepark with graffiti columns was not palatable to some of the older people who saw it as attracting bad behaviour, “whereas we saw it as a way of concentrating that behaviour so that they are not tagging letterboxes,” says Josh.

So, they suggested an induction day and inviting local artists from around region to launch the concept. “When we proposed our ideas [about a skatepark and graffiti cans] we were a little bit nervous. They agreed with us in the end.”

But they noted the residents’ strong sense of community, and that they “never came at it [the redesign] from a negative angle – they were always optimistic and proud of their community and wanted us to look at it from that perspective,” says Alicia. “We didn’t see ourselves as coming to fix up a dodgy area, we’re coming to build on what they already have and to invite wider Masterton to their community.”

While they had no budget, they were mindful of cost and of “not being too frivolous”. Josh says they had a mix of less costly ideas that could be achieved first, alongside more aspirational, larger-scale concepts that would require a bigger budget, such as a Māori university. This is a dream of Hohepa Campbell, the principal of Eastside’s Te Kura Kaupapa Māori. He envisages an education hub for ages 0 to 99 that could also serve the tertiary education needs of the wider region.

Incorporating Māori designs into urban settings as part of Masterton's Eastside redesign

Real-world experience a powerful incentive

The students say the project gave them valuable insights and experience. “It puts the pressure on to do a really good job when you have people out there in the community who are actually relying you to come up with something that’s a well-researched and a quality product. It just incentivised us to do a really good job,” says Hannah.

Alicia is pleased that the final result “reflects their vision and values and what they wanted, rather than us just coming in and dictating what our ideas and values are.”

Phoebe says the experience tested their listening and communication skills through having to deal with a wide variety of people who would often have different and sometimes contesting ideas of what they wanted.

Alicia noted that Eastside has “a deep cultural connection to the land and the river – we needed to engage their principles of Matauranga Māori (knowledge and wisdom) into our approach. It was something different we had to consider. A lot of our assignments are based on planning theory – words and scholarly stuff, so to weave those different aspects into this project was really cool.”

Josh says the project was “a really enjoyable process getting to know the community and working, not so much with professionals and powerful stakeholders, but just the everyday people who use the spaces.”

Passion for planning

Since they’ve completed their degrees, three of the four have jobs (two in Wellington consultancies and one in an Auckland consultancy), and Josh is going travelling. The aspects of planning they love and look forward to in their careers include dealing with a wide range of different people from all walks of life and getting to work on a wide variety of large and small projects for both councils and applicants. For Alicia, a “greenie”, being a planner means “being able to have some influence and do my bit to make the environmental impacts a little bit less than they otherwise would be.”

Their lecturer Associate Professor Imran Muhammad says the experience allowed the students to engage with a real-world community and stakeholders, which gave them “real passion for the project” and “a sense of contribution to the community”.

Aaron Bacher, community development advisor for the Masterton District Council, says; “the opportunity for the community to see a cohesive vision for their space cannot be overestimated. If we are to have vibrant flourishing communities and places in the future it has to come from within. In this co-design process between Massey’s urban planning and design course and Masterton’s Eastside neighbourhood, we can see a way to support this community-led process.”

“As someone who has been on both sides of a project like this as a student and now as a professional, I know there are huge benefits for each. The students get an opportunity to apply their creativity and abstract skills to a real project. The community gets fresh ideas, an outside perspective, and design thinking applied to the place they love and care about.”

Check out Masterton Eastside design here.

Planning students meeting with community members in Masterton's Eastside as part of the redesign process.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________