The Sustainable Nutrition Initiative (SNiTM), was proposed as part of the New Zealand contribution to the Food Systems Summit.

Feeding an increasing population sustainably is one of the big challenges of our time. So much so that the United Nations will later this year convene a Food Systems Summit, to launch bold new actions to achieve healthier, more sustainable and equitable food systems.

The Sustainable Nutrition Initiative (SNiTM), a research program in the Riddet Institute at Massey University, works on the same questions that will be asked at the Summit. Their DELTA Model was recently proposed as part of the NZ contribution to the Summit, in response to the call for “game-changing solutions” to achieve sustainable food systems.

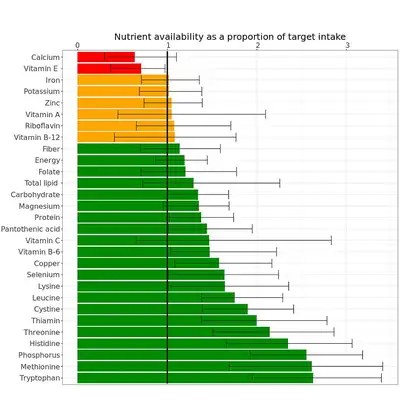

The model, recently published in the Journal of Nutrition, examines the nutritional side of sustainability: how does the world feed the world? It takes global food production, supply chain, and nutrient composition data to calculate the nutrients available from food. This is then compared with the nutrient requirements of the global population, to see where the gaps are in delivering nutrition.

The project is led by Riddet Institute Deputy Director, Professor Warren McNabb. “The DELTA Model has been in development for a number of years now, and it’s great to see the work come to fruition and be recognised internationally and by the NZ government.”

Riddet Institute Deputy Director Professor Warren McNabb

Perhaps the most useful feature of the model is its accessibility. “We decided to make the DELTA Model openly accessible on our website so that anyone can have the chance to explore the global food system, and see the importance of considering nutrition when thinking about food system sustainability,” says Dr Nick Smith, one of the Riddet Institute researchers on the project.

Some of the key results of the model so far include putting nutrient waste in context. We often think about the amount of food that is wasted, but less about the nutrients that go to waste as part of this. The DELTA Model shows that not all nutrients are wasted to the same extent, and that key micronutrients like calcium have very low waste.

The model can also be used to look to the future and test hypothetical scenarios for feeding the global population. “What we find is that the current food system produces enough of almost all nutrients to meet the needs of a much larger global population – we just don’t distribute it equitably. If we test scenarios that make sweeping changes to production systems, they usually fall short of delivering the micronutrients that the global population needs,” says Smith.

Dr Nick Smith

The DELTA Model is also used internationally, both in research and teaching. Both Wageningen University & Research (Netherlands) and Monash University (Australia) use the model as part of their Masters programs in nutrition and agriculture. Researchers at the University of São Paulo (Brazil) and the University of Lincoln (UK) also use the model in active collaborations with the Riddet Institute.

“The global food system is under justified scrutiny from an environmental sustainability perspective and needs to change. But it’s essential that the nutritional implications of any change are not forgotten. The DELTA Model is a tool to investigate future food system scenarios to see what is possible from a nutrition perspective, to be considered alongside the other aspects of sustainability”, says Dr Smith.

The team will continue to develop the model and grow their research. Future versions will include the environmental impacts of food production, such as land use, to give the user a more complete picture. The model is likely to continue to produce novel results useful for planning the future of the food system.

There is great variation in the amount of different nutrients available in different parts of the world. The coloured bars here show the global average availability of nutrients, against the black vertical line, which is the requirement. This shows that there is enough of most nutrients to meet the global requirement. However, the range bars show the variation in availability in the world's countries, many more of which fall below the requirement line.