Postdoctoral Fellow Dr Renata Muylaert.

Their study published in Nature Communications, has mapped important complex factors contributing to the risk of transmission of SARS-like coronaviruses from bats as primary hosts to humans. Their research offers insights into the spatial dynamics of coronavirus transmission risk and its implications for public health and land use planning to minimise zoonotic risk.

The emergence of SARS-like coronaviruses has become a global concern in recent years, with zoonotic transmission events at the forefront of discussions surrounding pandemic prevention and preparedness.

This research investigates the spatial variation of risk considering the multiple stages involved in the process, from wildlife reservoirs to human populations.

Professor Hayman says there are a number of interesting findings in this study.

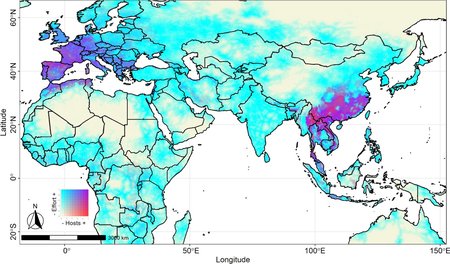

“There are multiple drivers of transmission risk. The research maps show three major drivers associated with the risk of transmission of zoonotic SARS-like coronaviruses cluster across space, namely landscape change, host distribution, and human exposure. Understanding these drivers is crucial for informed surveillance and mitigation activities.”

Another key finding is the correlation between direct and indirect transmission pathways.

“The study explores both direct and indirect transmission pathways by modeling four different scenarios, involving livestock and mammalian wildlife as potential reservoirs. These scenarios provide insights into how coronaviruses are circulating within ecosystems.”

Cluster analysis was also a main theme in their study. Lead author on the article, Dr Muylaert, says the research identified 19 clusters within a single country and 10 transboundary clusters that exhibit varying risk factor contributions.

“Each of these clusters show similar conditions occur with specific risk profiles, where clusters with the largest number of hotspots may point out to where spillover events are more likely to occur. High risk areas far away from public health facilities should be target of different prevention strategies than risk areas close to hospitals and clinics, as viral emergence and outbreaks may take longer to be locally detected,” Dr Muylaert adds.

Percival Carmine Chair in Epidemiology Professor David Hayman.

Further findings examined the implications for primary prevention and public health. China and Indonesia are highlighted as countries with clusters presenting the highest risk of zoonotic coronavirus transmission, but with considerable variation in the time to access to healthcare. The findings have global implications for stakeholders involved in land use planning, healthcare implementation, and One Health actions.

“This study provides a comprehensive framework for addressing the complex issue of zoonotic coronavirus spillover risk,” Professor Hayman says.

“By identifying key drivers, transmission pathways, and high-risk clusters, it equips policymakers, healthcare providers, and land use planners with critical information to inform strategies aimed at mitigating the threat of future pandemics.”

This study was funded by Massey alumni through a philanthropic donation from the Carmines.

The research paper, Using drivers and transmission pathways to identify SARS-like coronavirus spillover risk hotspots, has been published in Nature Communications and can be found here.

Related news

Mapping hotspots for bats may help scientists prepare for future bat-to-human viral outbreaks

A new research paper identifies locations of bats that may host coronavirus based on climate, native forests, and caves where these bats inhabit.

Massey delivering online learning to help Liberia battle emerging infectious diseases

The Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa killed thousands of citizens including doctors, nurses and midwives and now Massey is helping to design and facilitate online training for staff in Liberia so they can better understand emerging infectious diseases.

Predicting disease emergence from forest fragmentation

A Massey University team has developed new ways of predicting disease-hot spots, created by humans changing the environment, to help identify where and how society can mitigate the risk of infectious disease emergence, such as Ebola Virus Disease in Africa.